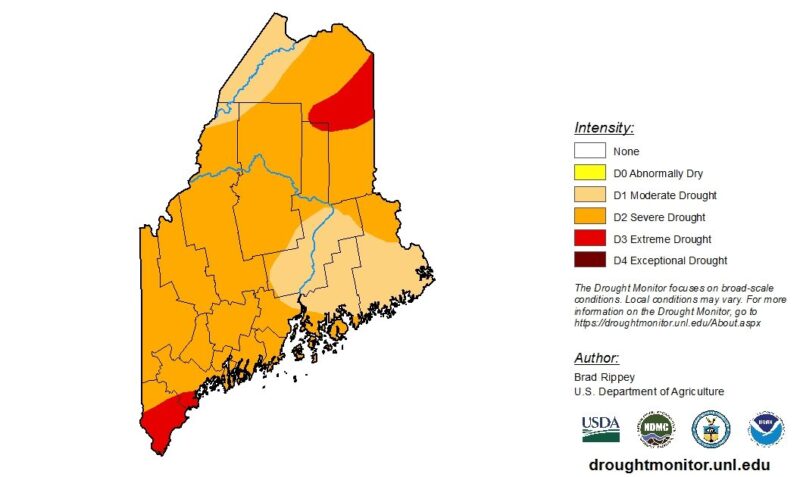

Following two months of severe drought, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) deemed Aroostook County a drought disaster area this week. The designation means farmers in Aroostook and neighboring Penobscot, Piscataquis, Somerset and Washington counties are eligible to apply for emergency farm loans from the USDA Farm Service Agency over the next eight months.

“It absolutely is the worst summer going back a long way,” said Dave Lavway, executive director of the Maine USDA Farm Service Agency. “All these programs are triggered now.”

Many rivers are at record lows and groundwater levels are going down, said Tom Hawley, hydrologist with the National Weather Service. “It’s really getting bad up here and getting worse every day.”

Declining surface water levels parallel conditions Maine experienced during historic droughts in 2001-02 and 2006, Hawley said, as well as a drought in 1947 that led to the worst fires in Maine’s history.

“It’s all interrelated once you get the lack of rainfall,” said Hawley. “The streamflow goes down, the groundwater goes down, farmers have trouble irrigating their crops, and crops end up suffering.”

Hawley echoed points made during a Maine Drought Task Force meeting Sept. 17 that acknowledged worsening drought conditions with no precipitation in sight.

“There’s really no rain in sight for the next week,” said Hawley. “The longer this goes on the worse it will be.”

The Bangor Daily News reported that Aroostook County farmers have been hit especially hard this summer by extreme weather patterns and crop failures. As drought conditions dry up water resources, interest among farmers to conserve water while supporting crop yields is high.

The USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) works with farmers to promote practices, including water conservation, using federal assistance from a separate program sponsored by the USDA.

“A lot of people are approaching me saying I want to be able to still irrigate but I need to use less water,” said Helena Swiatek, the USDA’s NRCS district conservationist in the Aroostook town of Presque Isle.

As severe drought forces farmers to adapt to less available water, Swiatek’s agency is pushing for them to switch to drought-resilient soil, which requires less water for irrigation.

“A healthy soil is much more resilient to the type of weather patterns we seem to be getting and it’s a better investment long-term because it’s not financially feasible to irrigate every acre,” said Swiatek.

To make soil more resilient, farmers must get more organic matter back in the soil, an effort the NRCS promotes through its Environmental Quality Incentives Program. Farmers interested in the program must sign up by Oct. 2 to qualify for 2021.

Extinction denialism undermines biodiversity protection

A new study highlighted in the news website Mongabay warns about extinction denialism as a new threat to the global biodiversity loss crisis. Three key types of extinction denialism are mentioned: literal, interpretive and implicatory.

Interpretive denialists look to cure the biodiversity crisis with economic growth.

“Environment deniers don’t buy into the fact that there’s limits,” said Dr. Amber Roth, assistant professor of forest wildlife management at the University of Maine.

One of Roth’s goals is to prevent species from getting on the federal endangered species list by working with industrial and private landowners to adopt management strategies that protect declining bird species — like the Bicknell’s Thrush and Rusty Blackbird — from being threatened while reaping economic benefits from their resources.

“If we’re going to think about everything from an economic perspective, it gets really challenging,” said Roth. “We’ve always had trouble quantifying ecosystem services, and we’ve always underestimated the value of trees, clean water and clean air.”

The array of cultural and ecological benefits that nature provides humans — known as ecosystem services — are hard to price but essential to balancing conservation and consumption. Ecosystem services provide space for biodiverse food chains to flourish and lucrative human supply chains to capitalize on a healthy environment.

Roth suggested that the complexity of the extinction crisis or climate change could be why people find it easy to shrug off environmental issues.

“If you don’t want to try to understand the complexity of it, you just pretend it doesn’t exist,” she said.

Penobscot Nation backs changes to waste management rules

Citizens and advocacy groups proposed changes to Maine’s waste management rules during a Board of Environmental Protection (BEP) meeting Sept. 17. They hope to eliminate out-of-state trash from ending up in Maine landfills and outline environmental justice rules into BEP regulations by amending the Department of Environmental Protection’s (DEP) Maine Solid Waste Management Rules.

Proponents argue the DEP’s definition of waste enables neighboring states to send their waste to Maine, where communities then bear the brunt of the pollution burden. Forty percent of the waste packed into Maine’s largest landfill — Juniper Ridge in Old Town— comes from out-of-state sources, according to Community Action Works, a pro-environment group.

In addition to communities in Old Town exposed to pollution from the landfill, the Penobscot Indian Nation does its fishing in the Penobscot River adjacent to the landfill. Nation members remain wary of the long-term impacts the facility will have on their hunting and fishing grounds.

“Maine has allowed hundreds of thousands of tons of out-of-state waste to be landfilled in our state simply by changing the legal definition,” said John Banks, the natural resources director for the Penobscot Nation, in a Natural Resources Council of Maine news release. “The result is that we’ve become the dumping ground for states to our south. It is time to correct this massive injustice.”

Sinking kelp to combat climate change

As the impacts of climate change in the United States have become more visible with deadly wildfires ravaging the West, disastrous downpours devastating the Midwest and stronger hurricanes churning in the Gulf Coast, investments in companies looking to mitigate climate change are becoming more common.

Running Tide Technologies, a Portland-based startup company, has expanded its scope beyond shellfish aquaculture into carbon sequestration — something its founders envisioned even before its formation in 2017.

“Carbon sequestration is an absolute inevitability,” said CEO Marty Odlin.

Running Tide plans to sequester massive amounts of carbon by growing and sinking kelp 1,000 meters below the ocean’s surface. The kelp will work as a carbon sink, storing away tons of carbon that can then be sold on carbon offset markets to meet increasing demands for carbon credits.

The technology allows Running Tide to sell carbon offsets to other companies or organizations looking to reduce their carbon footprint. Green investments boost climate credentials and have attracted prominent venture capitalists, including Silicon Valley’s Chris Sacca and Boston’s David Frankel, to provide seed money for the company, reported Whit Richardson of Maine Startups Insider.

Running Tide was also granted money from Shopify’s 2020 Sustainability Fund, which is committed, “to invest a minimum of $5 million annually into the most promising, impactful technologies and projects fighting climate change globally,” according to its website and reporting from Fast Company.

Odlin considered climate change the key risk factor he was trying to address with Running Tide and sees carbon capture technology as a way to reduce the risk of worsening climate effects.

“Everyone has a responsibility,” said Odlin. “It’s just work that has to get done.”