A huge challenge to Maine’s economic health is written on business signs and online job boards across the state. Through all of its landscapes – rural, suburban and urban – “Help Wanted” pleas are ubiquitous reminders that Maine is in the midst of an employee shortage that cuts across business sectors and promises to get worse.

Faced with this worsening workforce crisis, Maine businesses, cities, towns and legislators are increasingly looking to the legal immigrant population as a source of unskilled and highly skilled workers.

Most discussions about tapping into immigrant populations to strengthen the workforce focus on three groups:

- Refugees in the United States through the federal U.S. Refugee Resettlement Program

- Asylum seekers who have applied for asylum on U.S. soil

- Asylees who have been granted asylum

These populations face numerous barriers to employment, including:

- A lack of English language proficiency

- Credentialing roadblocks for professionals who want to do the work they’re trained for

- Unfamiliarity with U.S. work culture

The combination of too few workers, an aging workforce and a declining population is adding up to a stagnant economy. And that leads to less tax revenue, impacting the ability of the state and communities to maintain necessary services.

Recognizing the severity of the workforce crisis and its impact on economic growth, state legislators are introducing bills to address employment hurdles that immigrants face.

Some opponents of additional support for immigrant employment programs cite cost burdens and added bureaucracy, while others criticize efforts that favor what they consider “outsiders” over “native” Mainers.

Advocates of more support argue that maximizing legal immigrant participation in the workforce is an important part of economic development efforts to build a sustainable workforce critical to the state’s future.

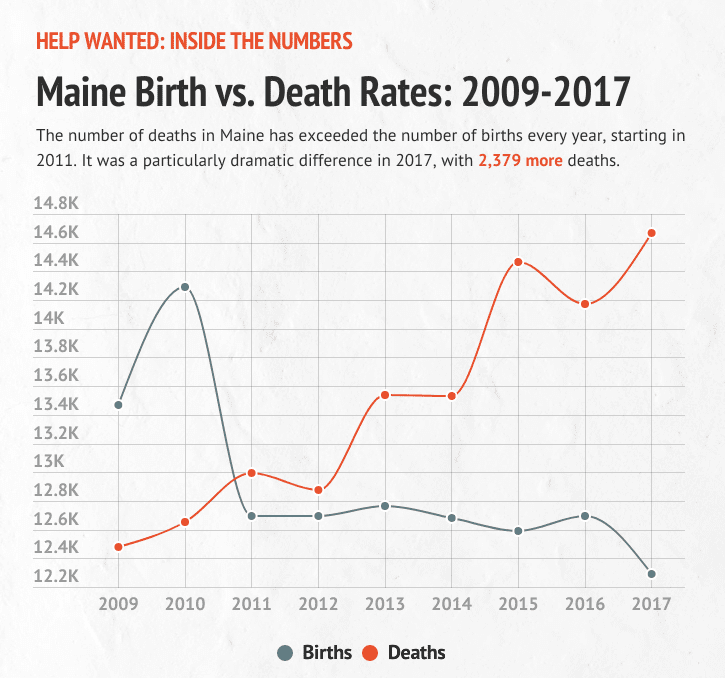

“Businesses in Maine are now more aware and are looking at the big picture,” says Beth Stickney, executive director of the Maine Business Immigrant Coalition, a nonprofit that helps to integrate immigrants into the Maine workforce. “The chambers, CEOs and the economists are saying we have a big problem and that immigration has got to be part of the solution. Maine’s birth rate is less than our death rate. We need to get people from elsewhere. How many people can we get from Boston or California versus immigrants who are already here or are coming here because a family member is already here?”

A case for clearing obstacles

Anaam Jabbir’s experience illustrates employment hurdles that immigrants face and how support can help them succeed. A refugee from Iraq, Jabbir and her family first settled in Georgia. They moved to Maine in 2009 because she heard that the schools are better in Maine. Unable to work as a teacher because her degree was not accepted in the United States, she worked in hospitality and in her family’s restaurant before entering a stitcher training program based in Westbrook.

Today, she’s the head stitcher and union chief at American Roots, a growing company that makes fleece clothing in the historic Dana Warp Mill in Westbrook.

“We need to encourage people to work with immigrants to give them a chance,” she says. “Some of them have degrees, experience. (Businesses should) let them have a chance to work. I think most of them are good workers, and they need to work hard to support their families.”

However, discussions about workforce training such as Jabbir’s often are derailed by the polarizing national debate that typically focuses on immigrants who aren’t legally in the United States. And changes in federal immigration rules have made it much more difficult for immigrants to come to the United States, thereby cutting the potential labor pool for the entire country and increasing competition between states for workers.

Maine’s daunting workforce challenge

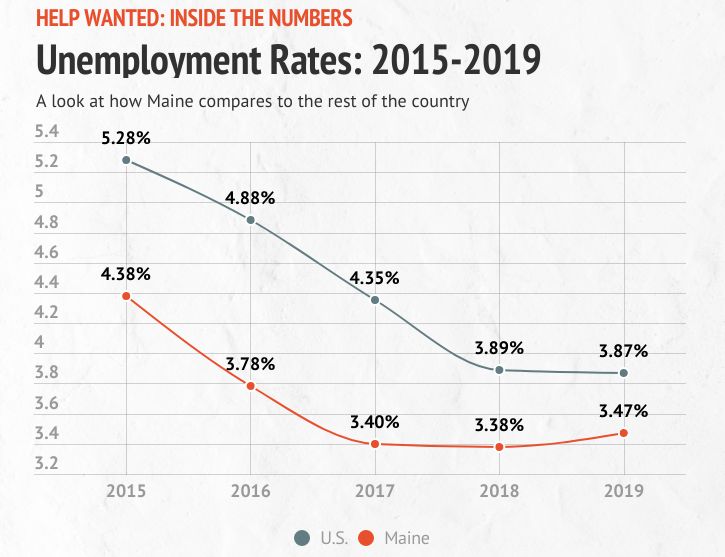

How dire is the workforce situation for Maine, which has a current unemployment rate of 3.4 percent?

Maine economists looking at the numbers use words like “cliff” and “tsunami” – not their typical vocabulary.

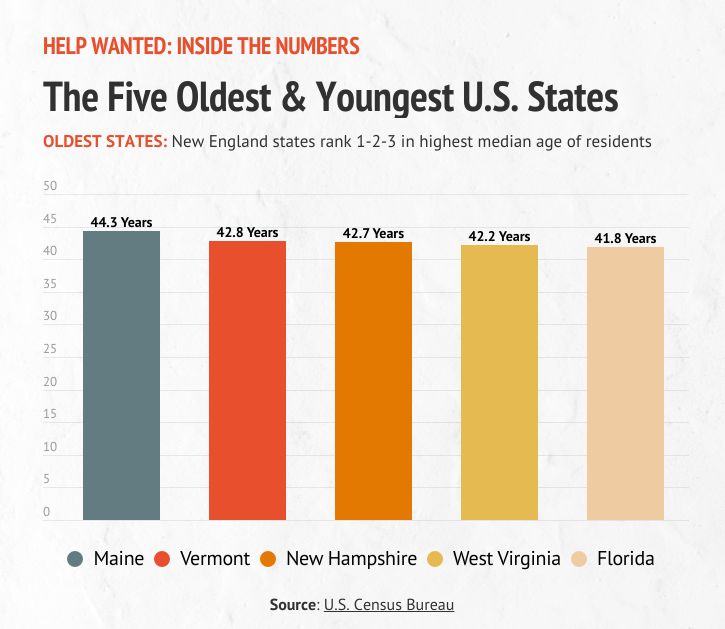

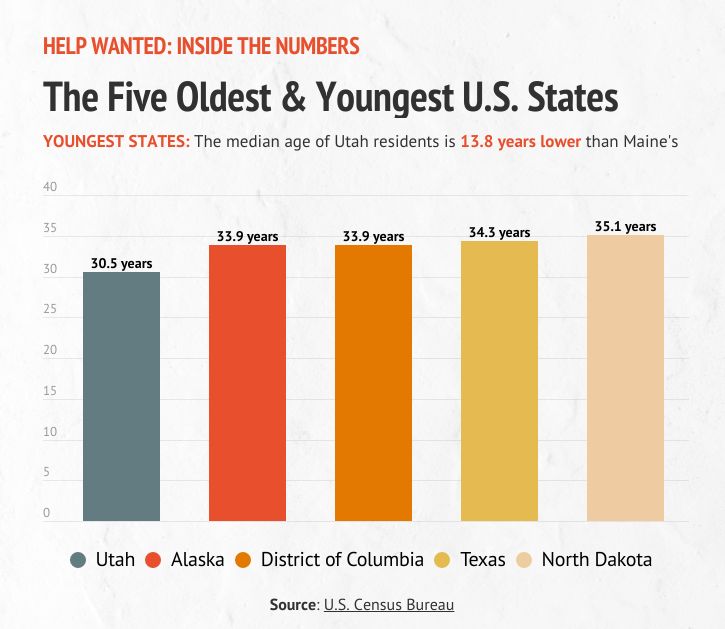

For years, economists have warned that Maine faces a severe workforce shortage because of a double whammy: declining birth rates and an aging population of Baby Boomers. In fact, according to the U.S. Census, Maine is the oldest state in the nation, with a median age of 44.3, compared to the national median of 37.08. In the race to the grayest in the U.S., Maine is closely followed by Vermont at 42.8 and New Hampshire at 42.7.

Charles Colgan, a professor emeritus at the University of Southern Maine’s Muskie School of Public Service and former state economist, has been warning about a workforce crisis for years. He explains that the current problem will get worse and become critical starting in the 2020s.

“By the end of the 2020s, with the age imbalance with no in-migration (whether foreign born or Americans moving here from other states), Maine’s population starts to fall as a whole everywhere – and rather rapidly through the 2030s,” Colgan says. “In my no-migration forecast, we go from a population of 1.3 million to about 1.1 million. An economy with about 200,000 fewer people in it is going to be a lot smaller. We are still at the leading edge (of the problem). The sheer process of aging means that the worst of it is still a decade away.”

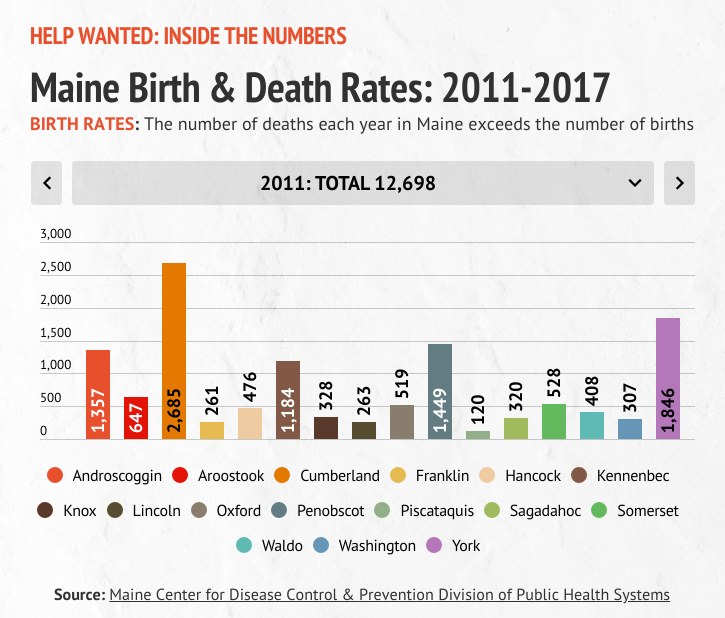

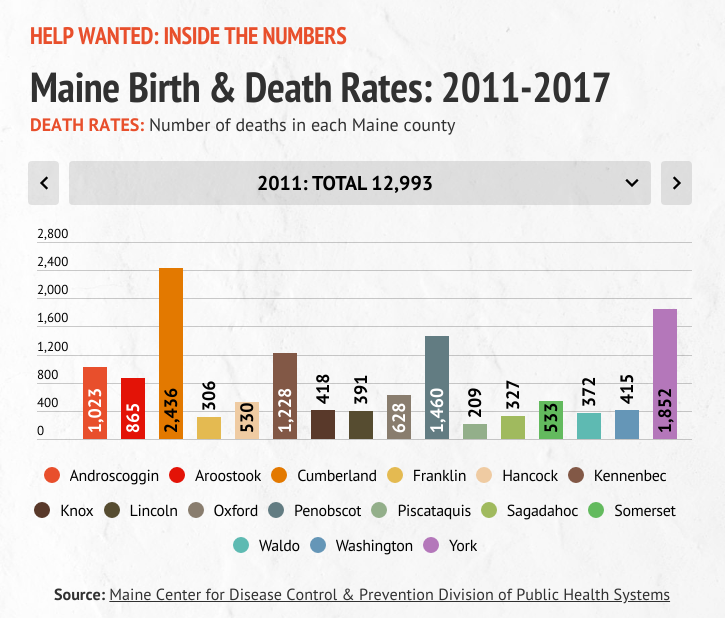

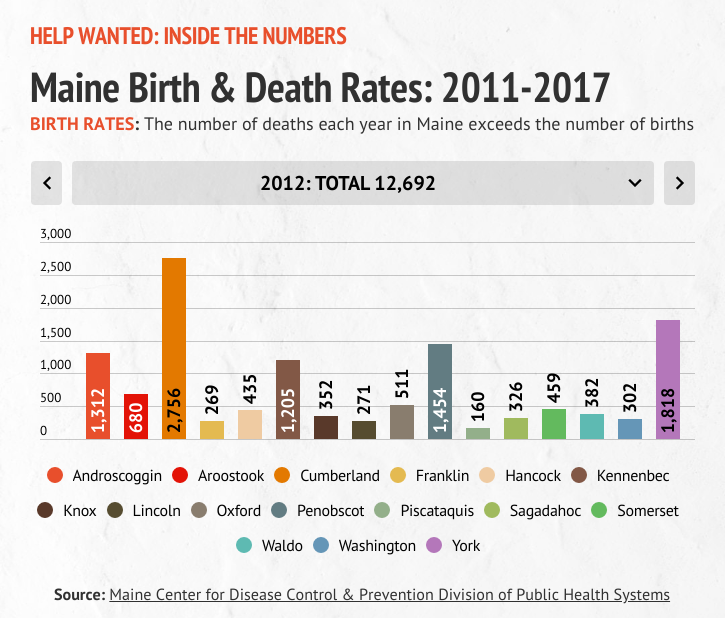

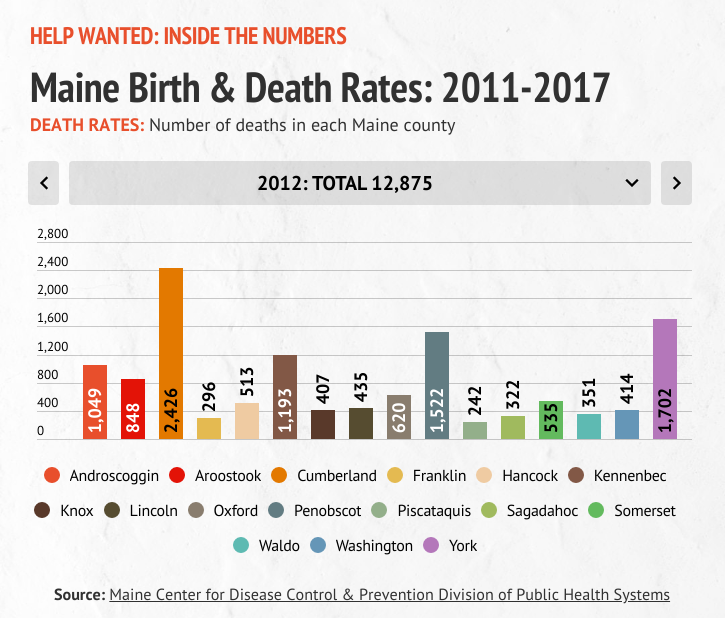

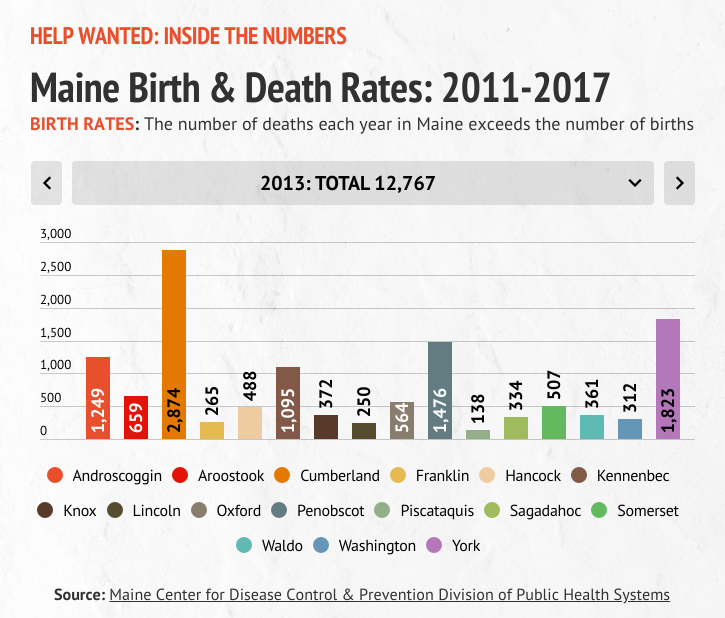

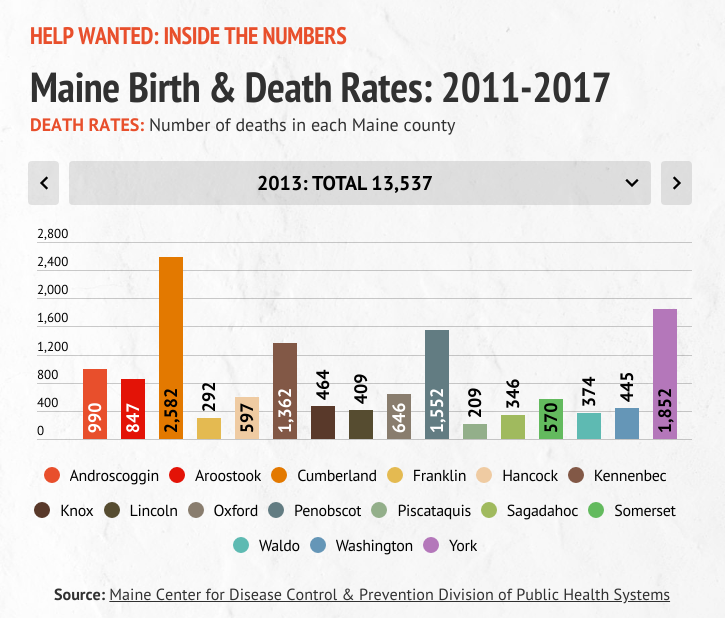

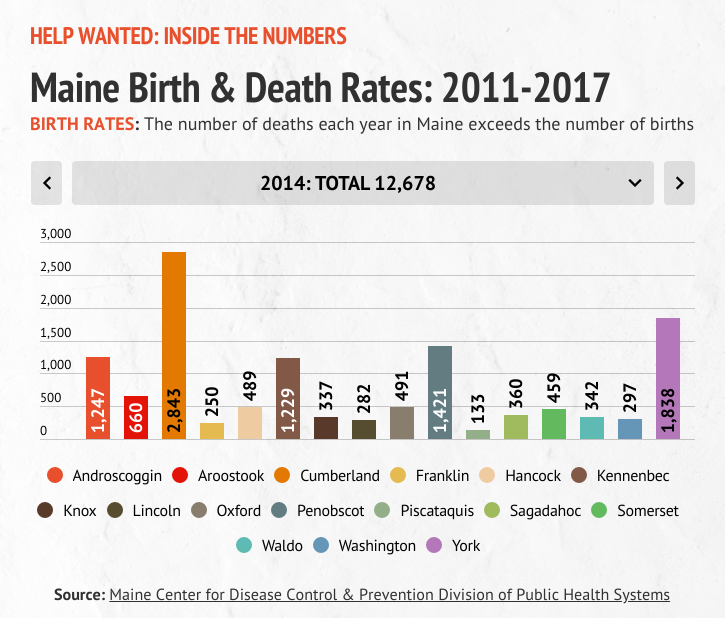

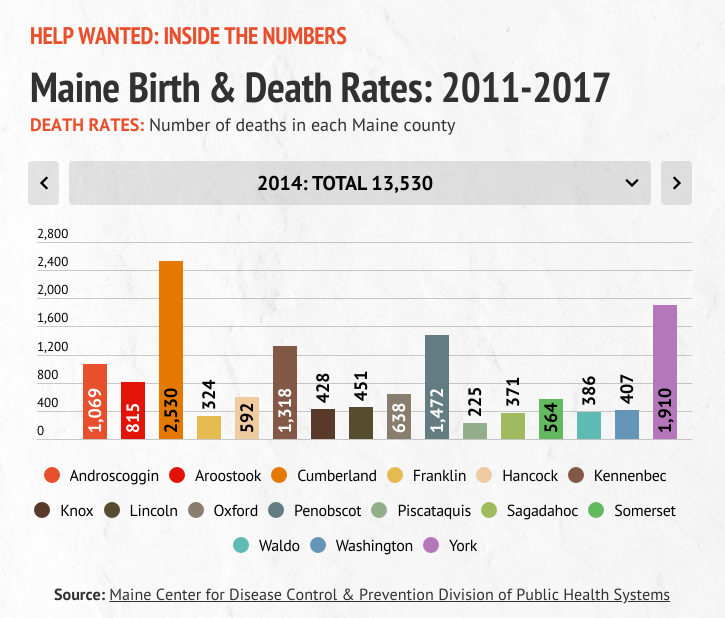

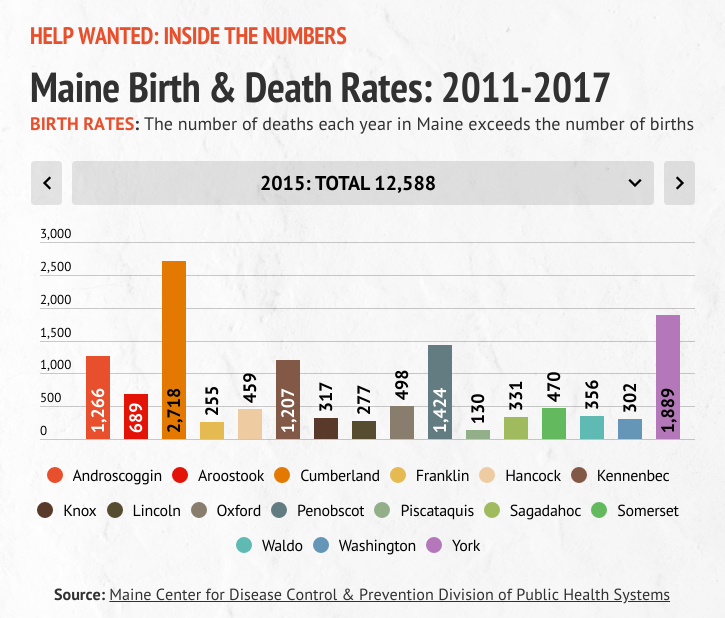

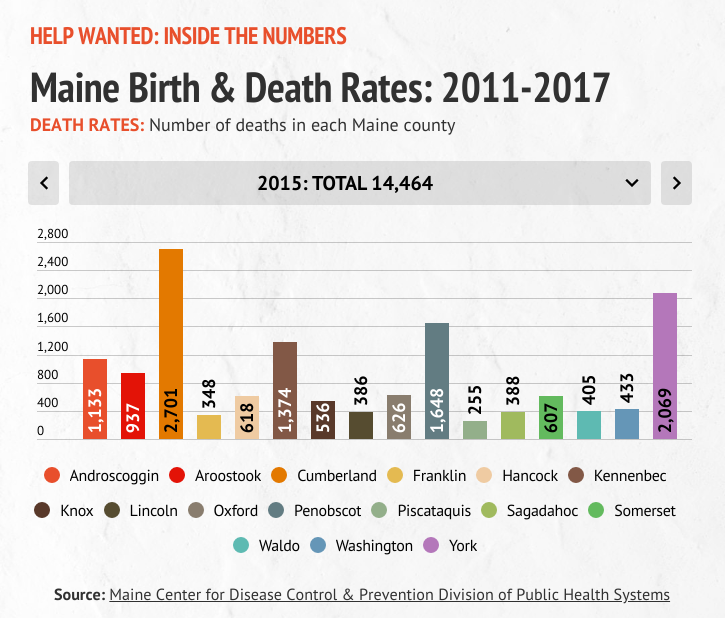

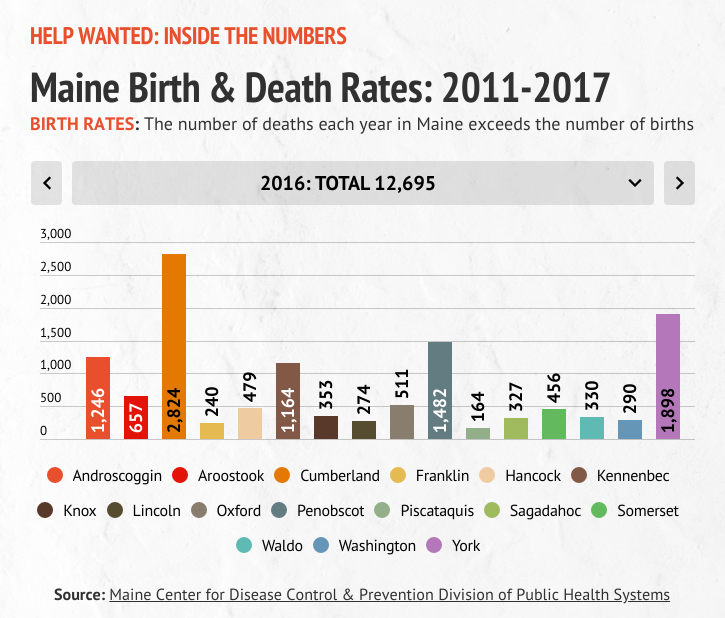

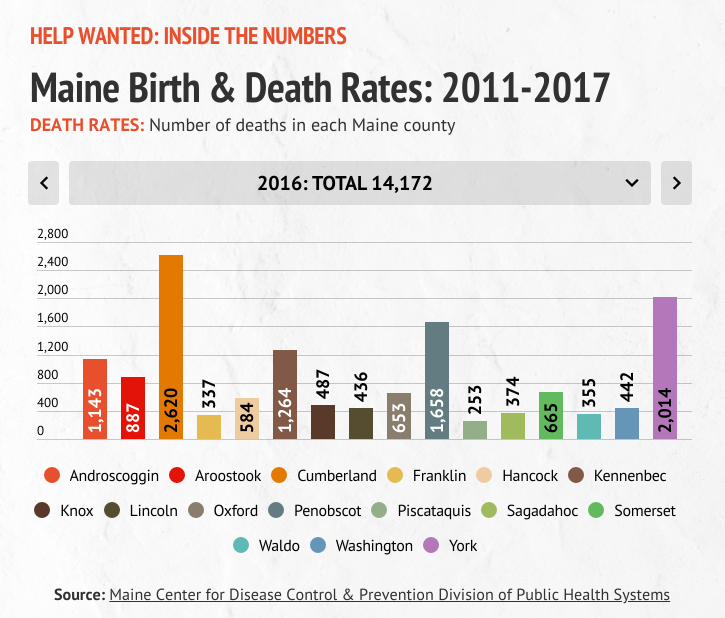

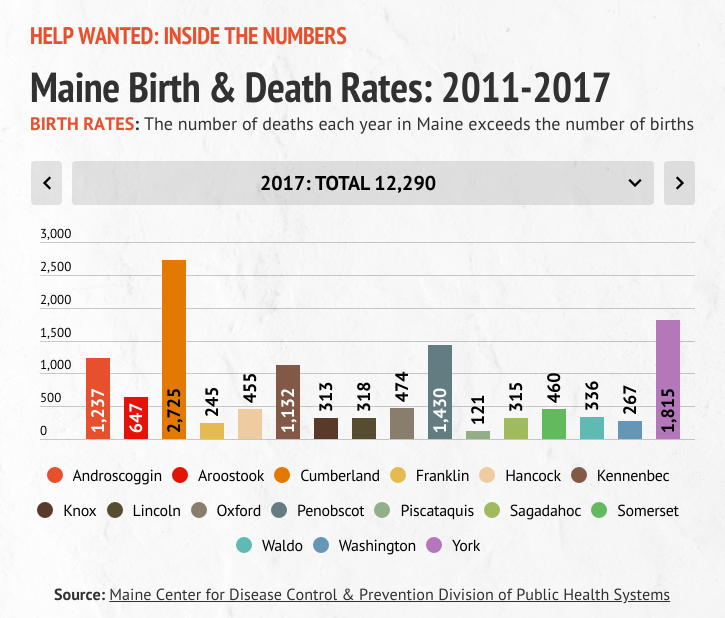

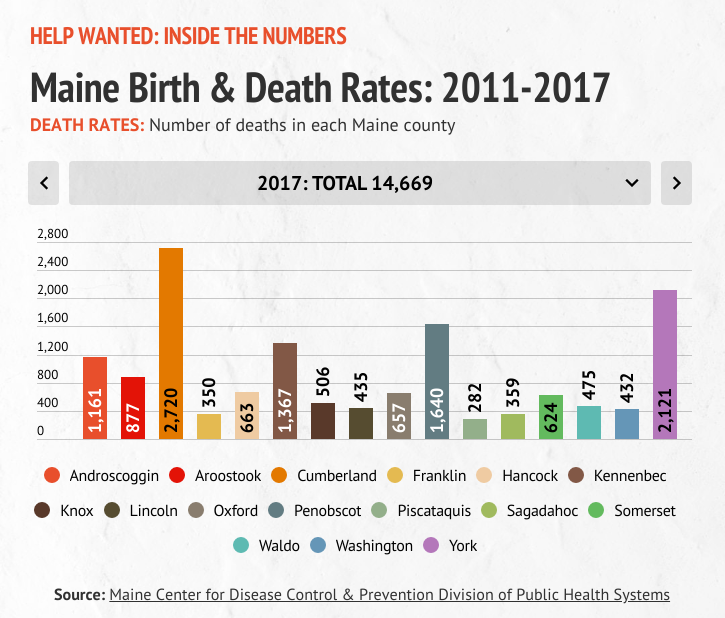

An overview of data adds to the grim picture. At the heart of the problem is that Maine’s death rate has exceeded its birth rate since 2011.

In 2017, the latest year with complete data, there were 14,669 deaths in Maine compared to 12,290 births, a negative differential of 2,379, according to the Maine Department of Health and Human Services.

The crisis has sparked reports that take a hard look at Maine’s aging workforce and demographics of the state’s immigrants. These reports include: Coastal Enterprises, Inc.’s “Building Maine’s Economy, How Maine Can Embrace Immigrants and Strengthen the Workforce,” the Maine Chamber of Commerce’s “Maine’s Labor Shortage: New Mainers and Diversity,” and the city of Lewiston’s “Immigrant and Refugee Integration and Policy Development Working Group Final Report.”

The data highlight the depth of the problem:

- Workforce projections of little or no cumulative job growth

- An increasingly aging population in terms of age distribution, with Baby Boomers heading into retirement and dragging age demographics further into the gray zone.

The net result is clear – fewer workers for open jobs. Although low unemployment numbers often are touted as a positive, those low numbers aren’t necessarily a good thing for the economy when they translate into a sustained labor shortage that hinders growth.

“The total growth in the economy is simple; it’s the number of employees times their productivity,” explains Colgan. “If the number of employees keeps going down, you can’t grow, unless productivity expands enormously, which doesn’t tend to happen in our economy. Eventually, it hugely slows the growth in the whole economy. That affects public revenues and virtually everything else. So, while a low unemployment rate is a good thing, a low unemployment rate caused by a permanent worker shortage as opposed to a temporary one is not a good thing because it becomes a primary constraint on the ability of the economy to grow.”

Colgan goes on to explain that while technological advances like automation may help offset some population/workforce challenges, the impact may not be enough to effectively counter the state’s birth and death rate gap: “Technology may just offset the effects of population decline so that the economy stagnates but does not grow, meaning there is little in Maine to attract anyone to come here or invest here. The result would be a downward spiral in output, employment, profits and population that would continue for some time.”

The impact of such economic stagnation and too-few employees is far reaching.

Topping the list is lost tax revenue, which drives state budgets and the services the state can afford. The result: “There are going to be some real constraints here in terms of our fiscal picture because of the lack of economic growth,” says John Dorrer, former director of Maine’s Center for Workforce Research and Information and co-author of Coastal Enterprises, Inc.’s report on immigrants and the Maine workforce.

Dorrer asserts that the state won’t be able to provide needed services because of reduced tax revenue.

“If this persists much longer, not only will you have a weakened GDP over a longer period of time, there could be an economy in reverse. It means that we aren’t going to get the kind of tax receipts that we need to improve and to provide the kind of services that Maine people want,” he says. “That’s a fairly immediate impact. Unless we grow the tax base, we are going to have a hard time sustaining the kinds of budgets that we are putting forth now. And with the aging population, there’s going to be an even greater need for more services.”

If the state doesn’t have the income tax revenue needed to make ends meet, more pressure could be put on strapped towns to increase property taxes.

“And how are we going to finance (the services)?” asks Dorrer. “How are we going to pay for it? How are we going to sustain an increasingly aging population that is the target of this tax shift and tax shaft thing that we are doing – where we continue to cap income taxes and shift the burden to property taxpayers. But people on fixed incomes are only going to be able to pay so much in property taxes.”

The workforce crunch is not only impacting existing employers and state revenues, it’s also putting a damper on businesses that are considering expanding in or into Maine, says Dorrer.

“We’ve had companies looking at Maine’s demographics and seeing the graying workforce, and instead of making expansion here, they have opted to go away,” he says. “Once those high-skilled jobs and high-wage jobs leave the state, it’s a significant loss.”

This workforce problem is not exclusive to Maine.

“If people aren’t exposed to minorities and other cultures, Maine will be out of it in terms of what’s happening demographically in the rest of the country,” says Carla Dickstein, Coastal Enterprise’s senior vice president of research and policy development and co-author of the organization’s report on the potential of Maine’s immigrants.

“Certainly New Hampshire is competing, as are most of the New England states. Everyone is looking for population. We are all competing. If we aren’t welcoming and supportive and doing what we can, then we can’t compete successfully.”

At the legislative level, despite the current political polarization, neither Democrats nor Republicans dispute the forecasts. The difference between the parties rests with how best to tackle the crisis and how important it is to tap into the pool of immigrant workers. Advocates for increasing efforts to integrate immigrants point to the availability and demographics of Maine’s immigrant population.

Which immigrants can legally work?

So, who are the immigrants at the center of efforts to grow Maine’s workforce? And how do they compare with Maine’s non-foreign-born workforce? The focus is primarily on two groups:

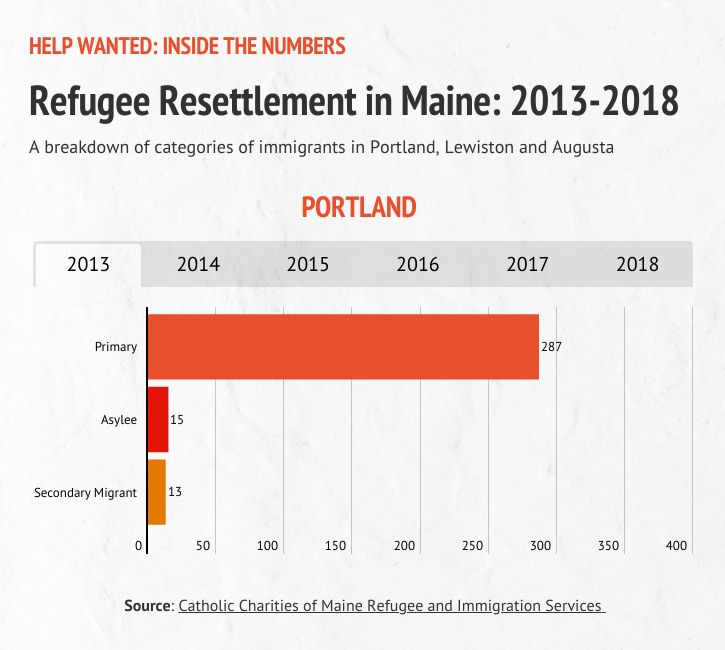

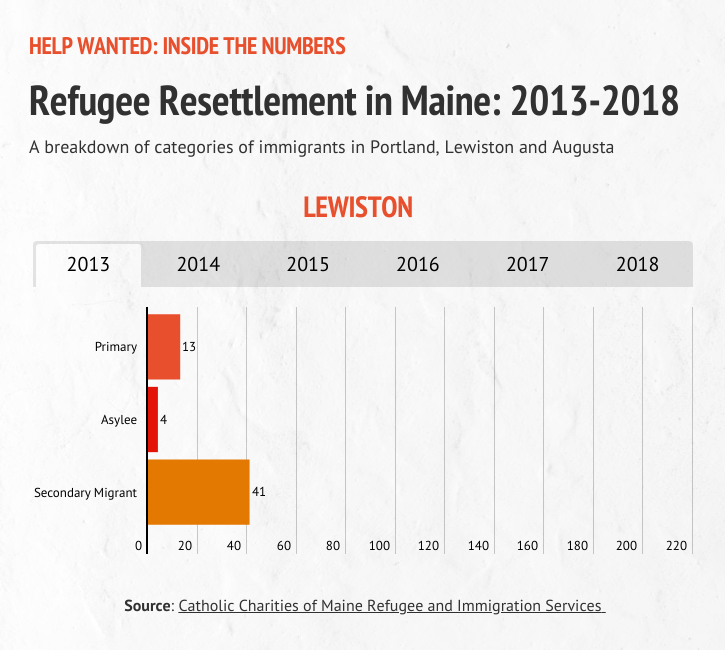

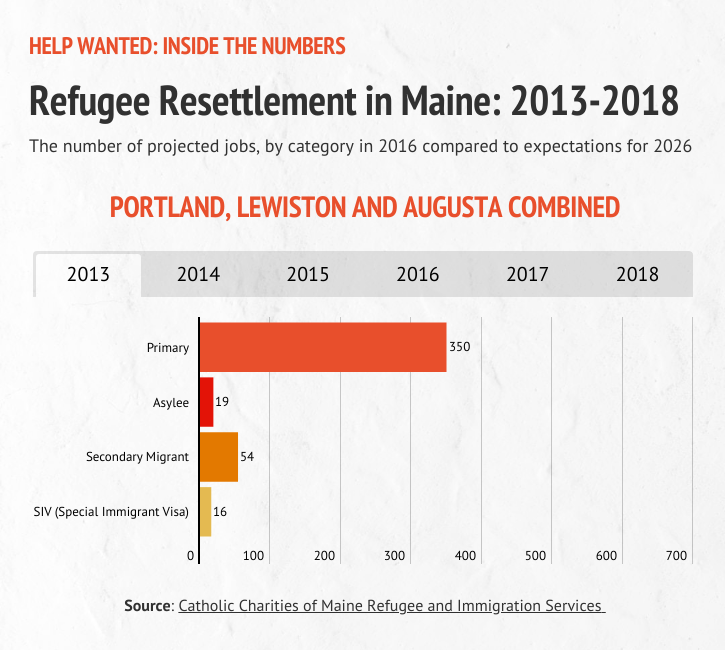

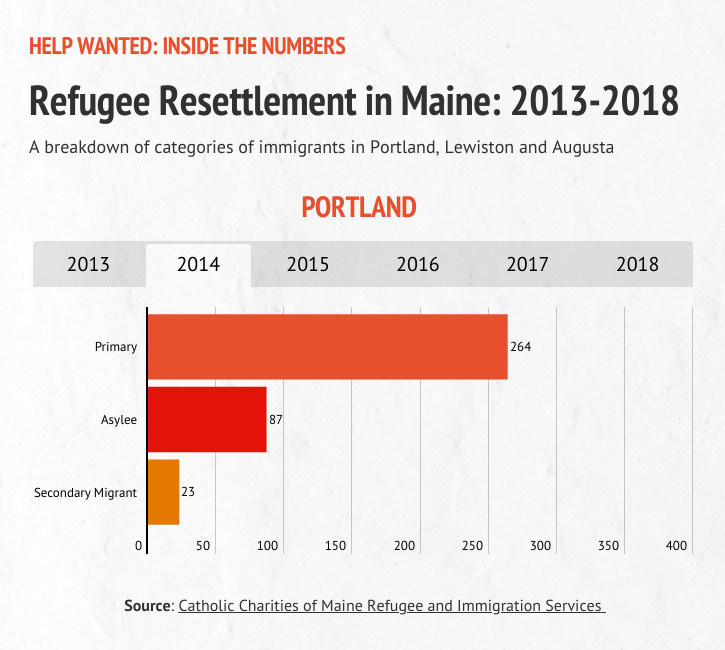

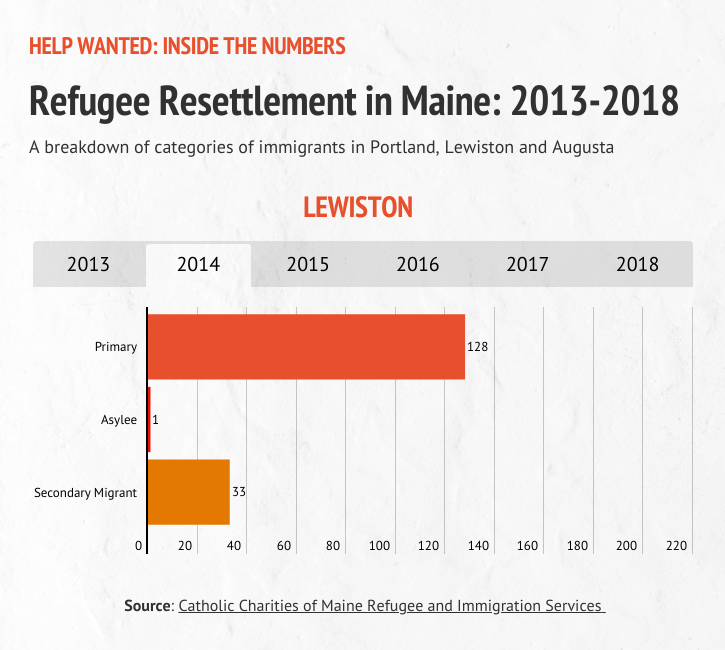

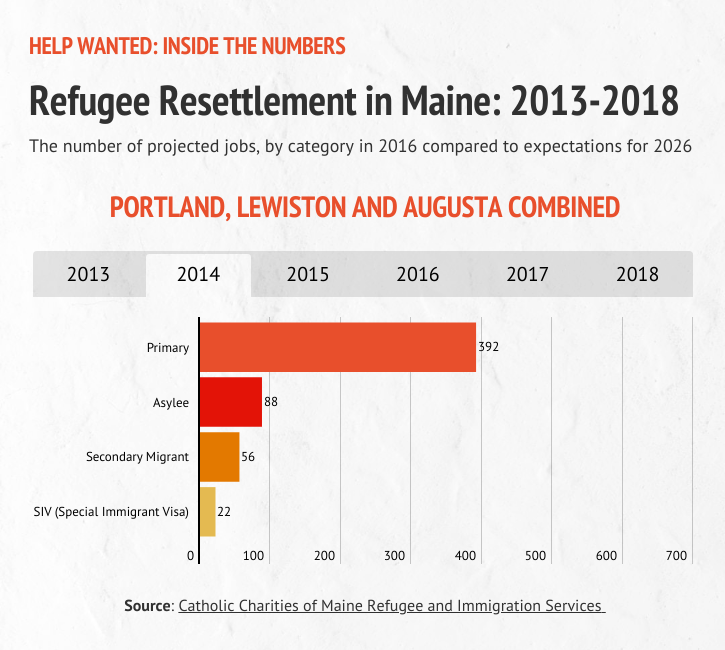

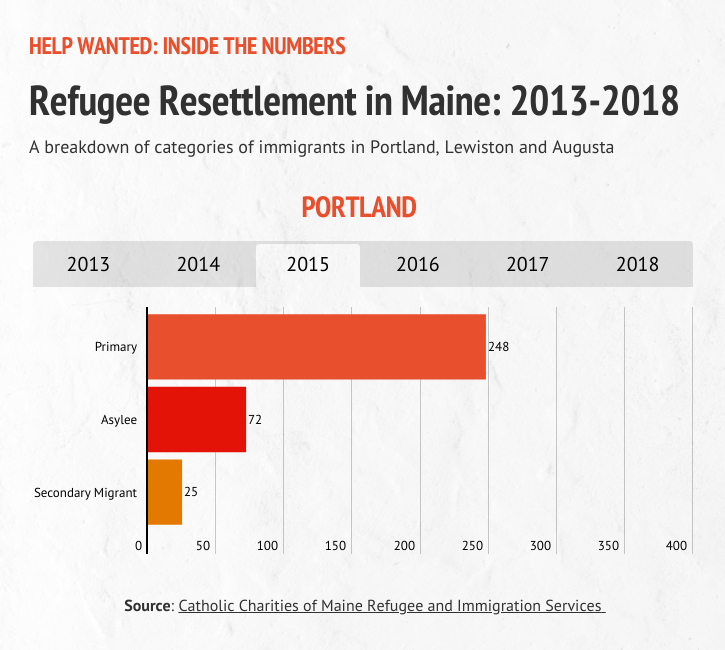

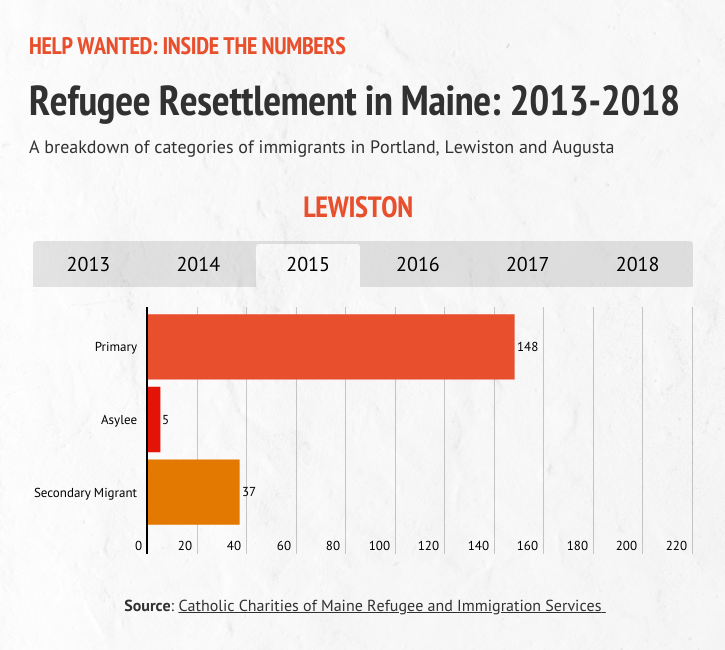

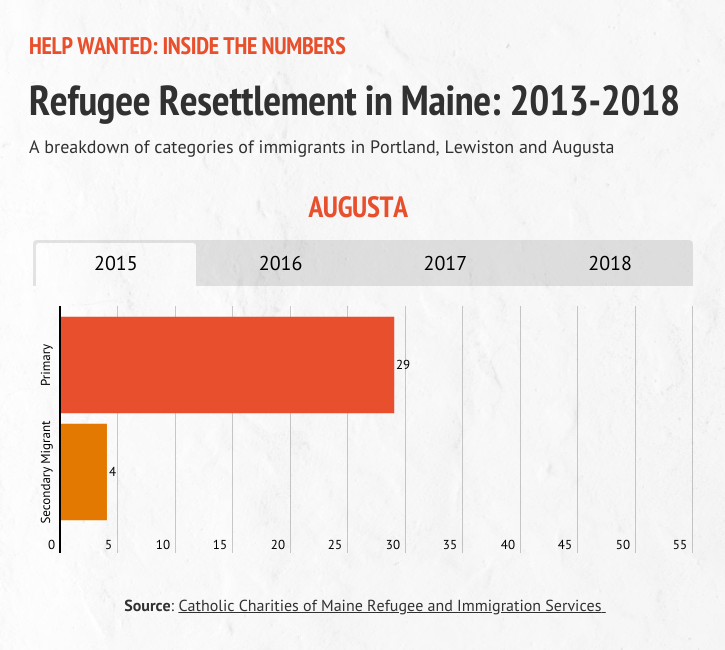

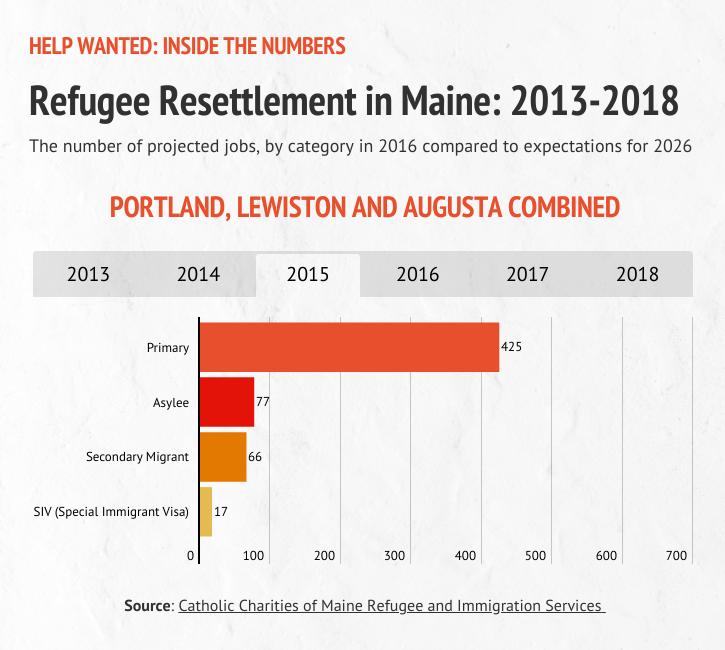

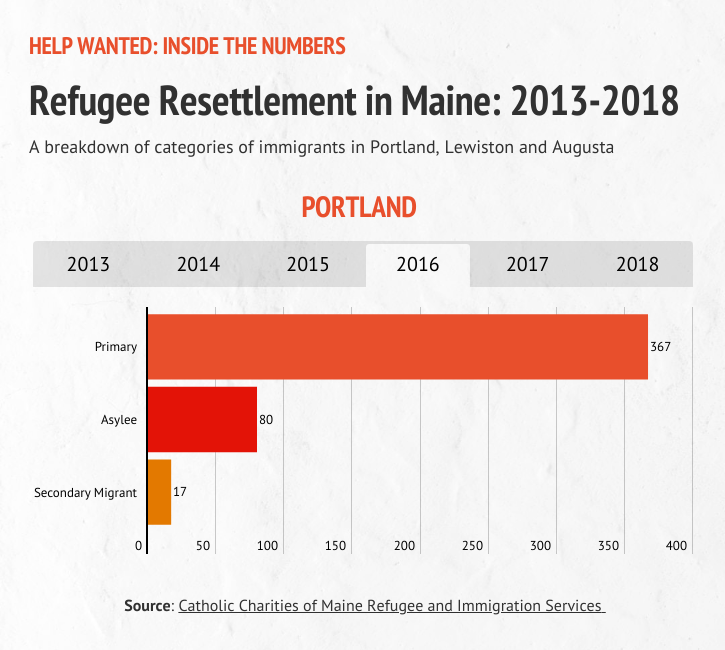

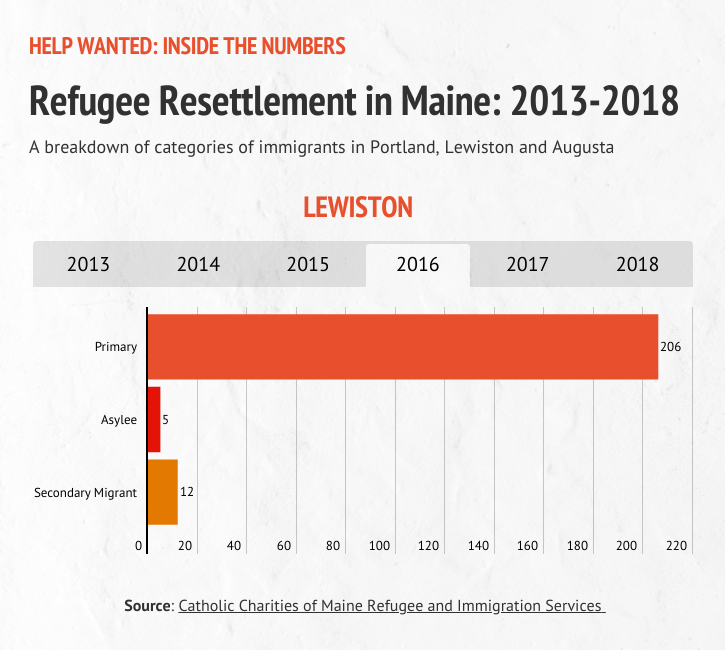

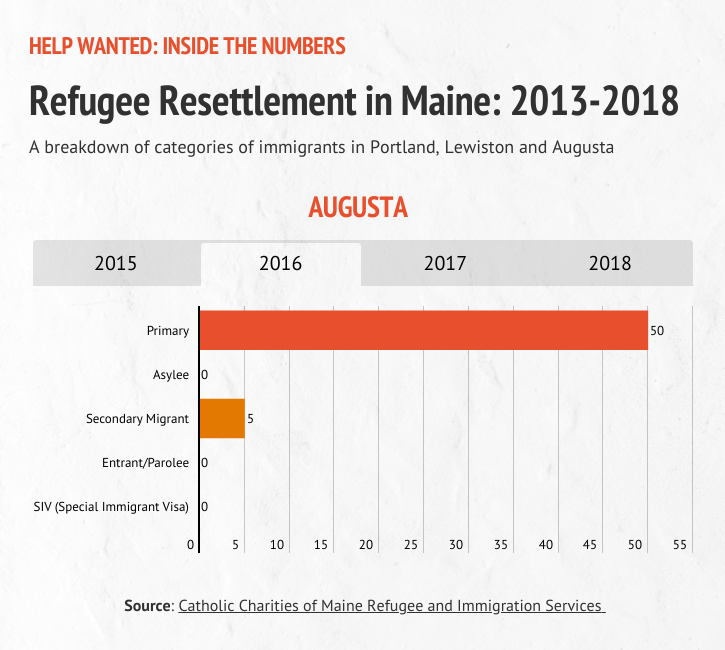

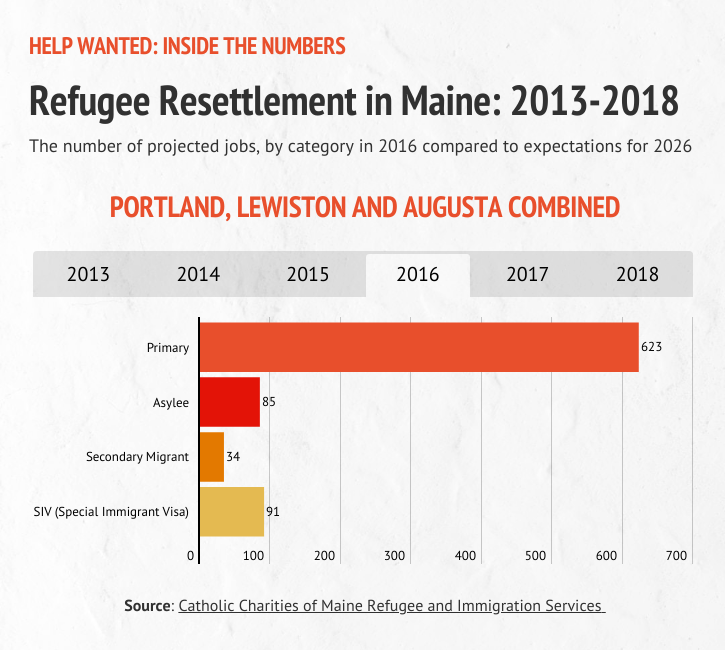

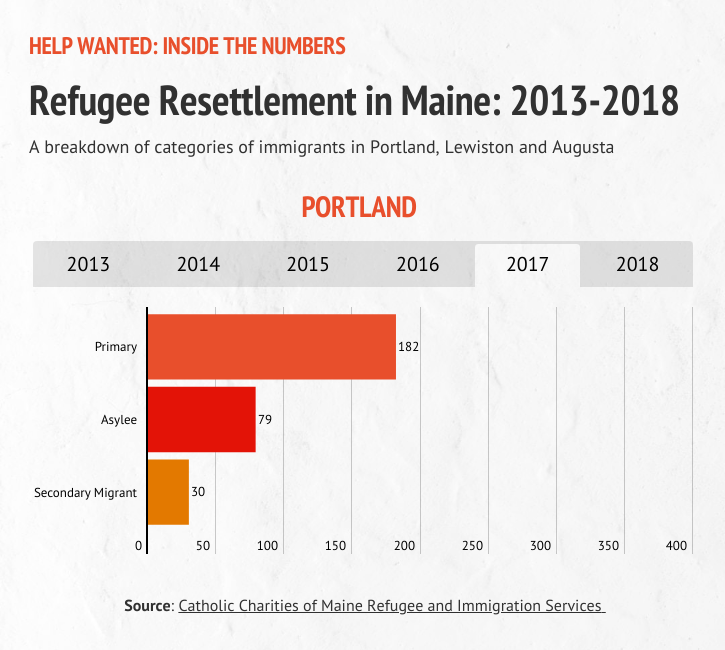

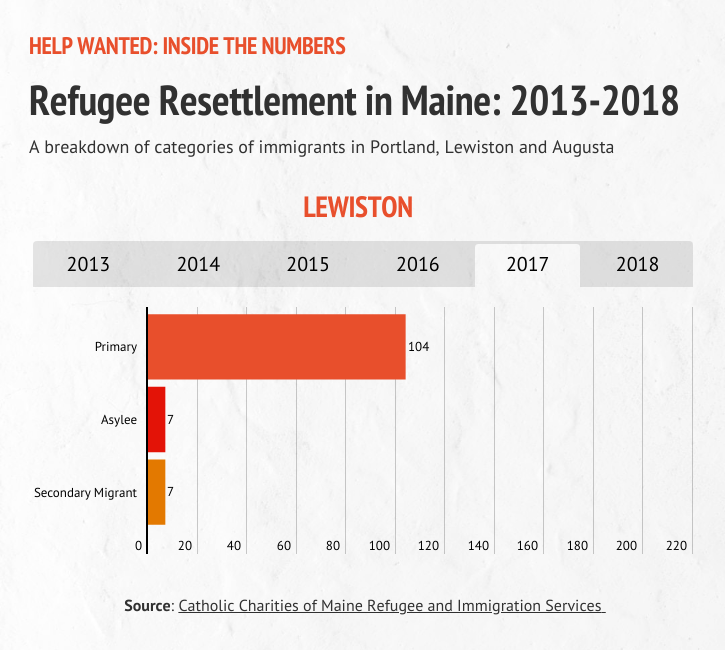

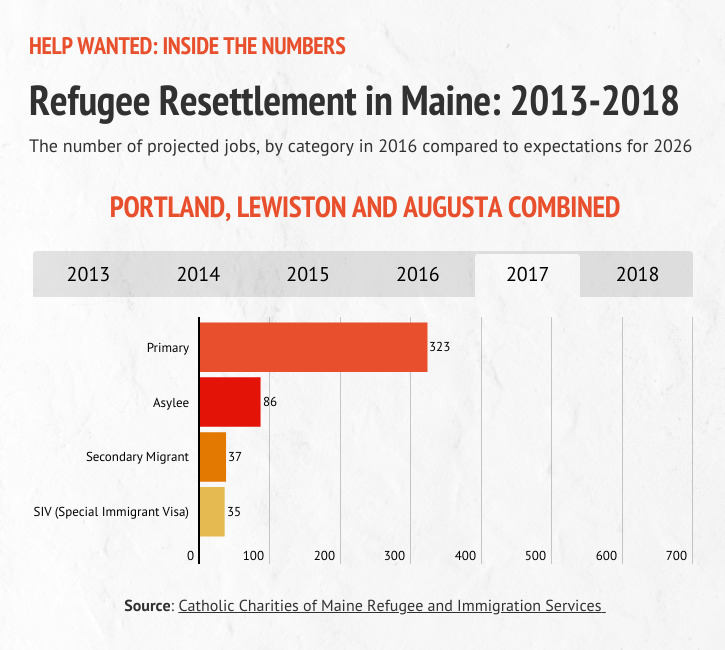

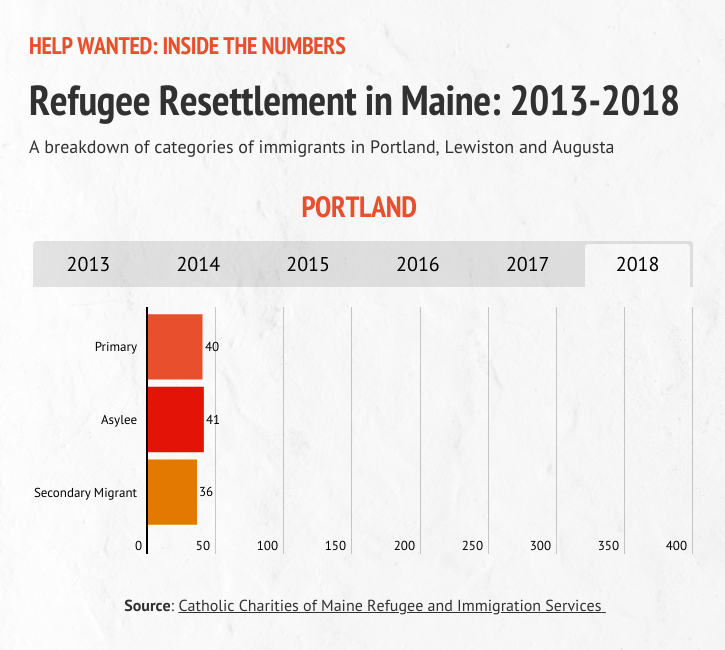

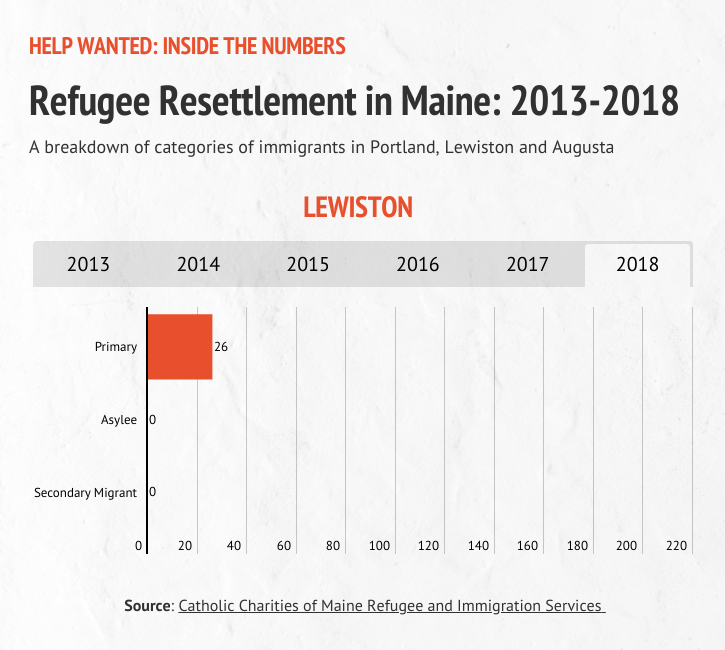

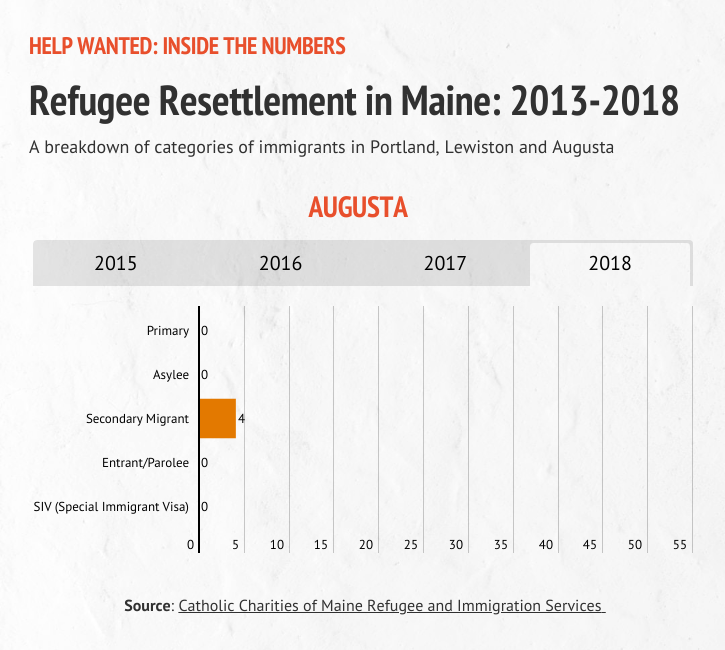

- Refugees: These are people who enter the country through the U.S. Refugee Resettlement Program. In Maine, this program is administered through Catholic Charities Maine. Refugees apply in their native countries. Those selected receive federal aid that’s coordinated through entities such as Catholic Charities.Refugees are eligible to work as soon as they arrive. Those who start out in Maine are called primary refugees; refugees who first settle elsewhere in the United States and then move to Maine are called secondary migrants. Secondary migrants move to Maine for various reasons, including a belief that it’s safer here than in urban areas like Atlanta or Philadelphia.

- Asylum seekers/asylees: These are people who have applied for asylum while in the United States or they have been granted asylum. After applying for asylum and waiting six months, asylum seekers are allowed to work as they await a final decision on their case, a process that can take years because of the current backlog of asylum hearings.Unlike refugees, asylum seekers do not receive federal support. In Maine, asylum seekers can receive general assistance, and once individuals are granted asylum they can receive federal support via Catholic Charities.

Quantifying the numbers for these populations is difficult, if not impossible. The U.S. Census does not ask about citizenship status. Rather, it asks whether respondents are “foreign born,” a designation that includes naturalized citizens, people in the country illegally, asylum seekers, refugees and others. (The Trump administration is trying to add a citizenship question for the 2020 Census – a contentious issue that’s now in the courts.)

Looking at limited data available through the Census, Maine’s foreign-born population is well below the national average, in terms of total numbers and percentage of state population. Maine’s foreign-born population is 3.6 percent, placing it 44th among the 50 states. And compared to the rest of New England, Maine has the smallest foreign-born population, too.

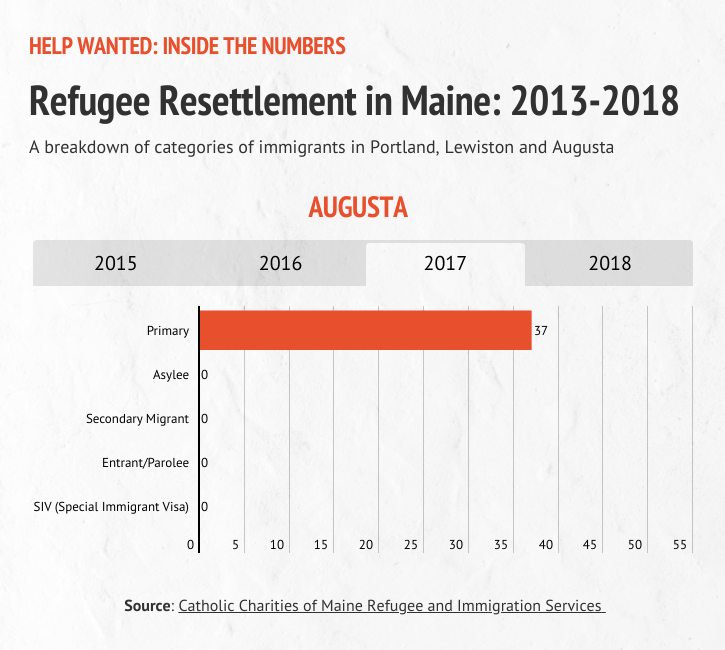

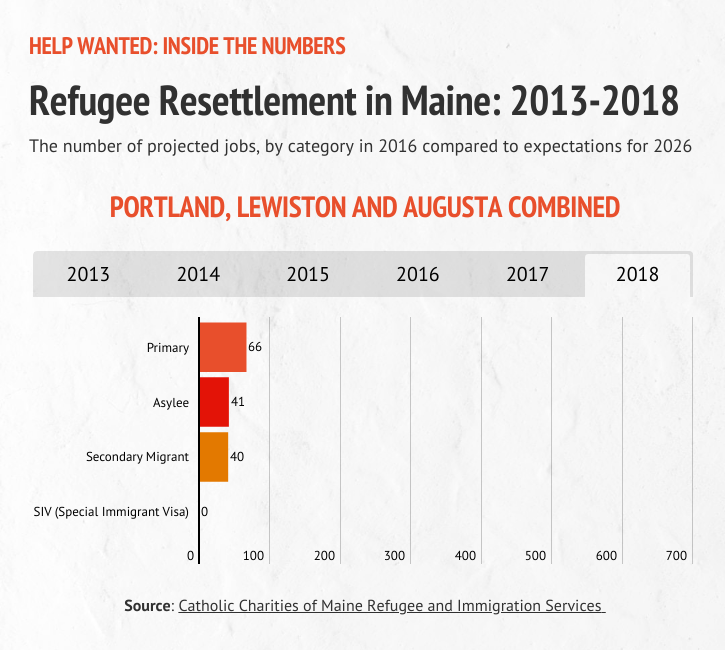

The best guide to tracing the number of refugees in Maine comes from Catholic Charities Maine, which says 66 primary refugees were resettled in Maine in 2018, and 40 secondary migrants (refugees who initially settled elsewhere in the United States before moving) and 41 asylees received assistance. Similar numbers are expected in 2019, says Hannah DeAngelis, director of Catholic Charities’ Refugee and Immigration Services.

According to Catholic Charities Maine, in the last 40 years, the federal refugee program in Maine “has assisted nearly 10,000 people through its resettlement program and assisted over 20,000 with refugee and asylee support services.”

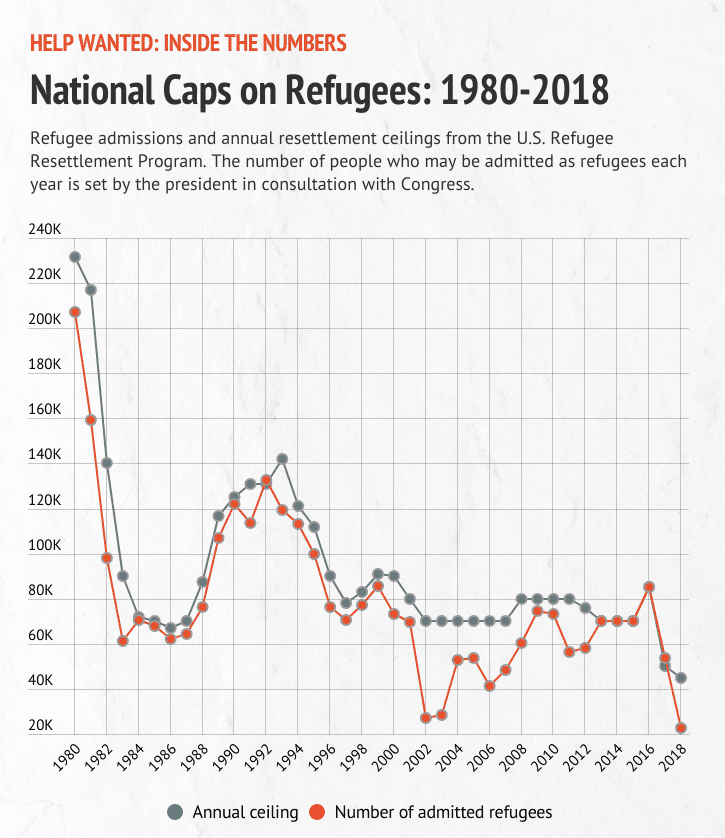

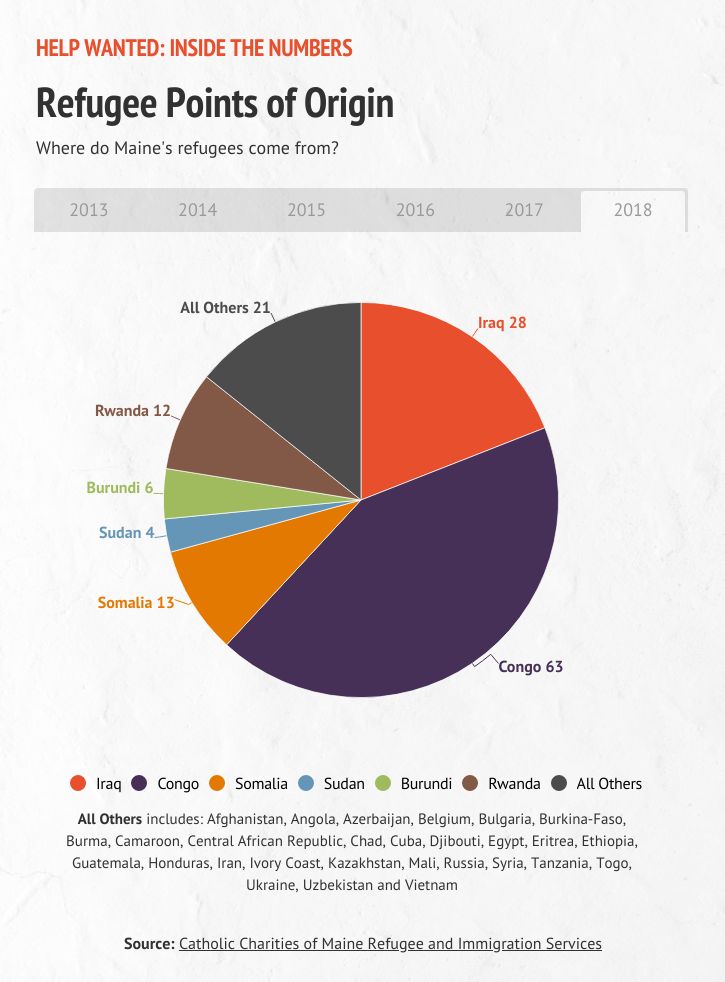

The number of refugees resettled yearly has dropped dramatically in the past two years because of the Trump administration’s reduction of refugee caps, and those numbers are reflected in a slowing of refugee resettlements in Maine. The current federal cap of 30,000 refugee admissions, the lowest on record, is down from 45,000 in 2018. Historically, the number of refugees admitted has been less than the actual cap.

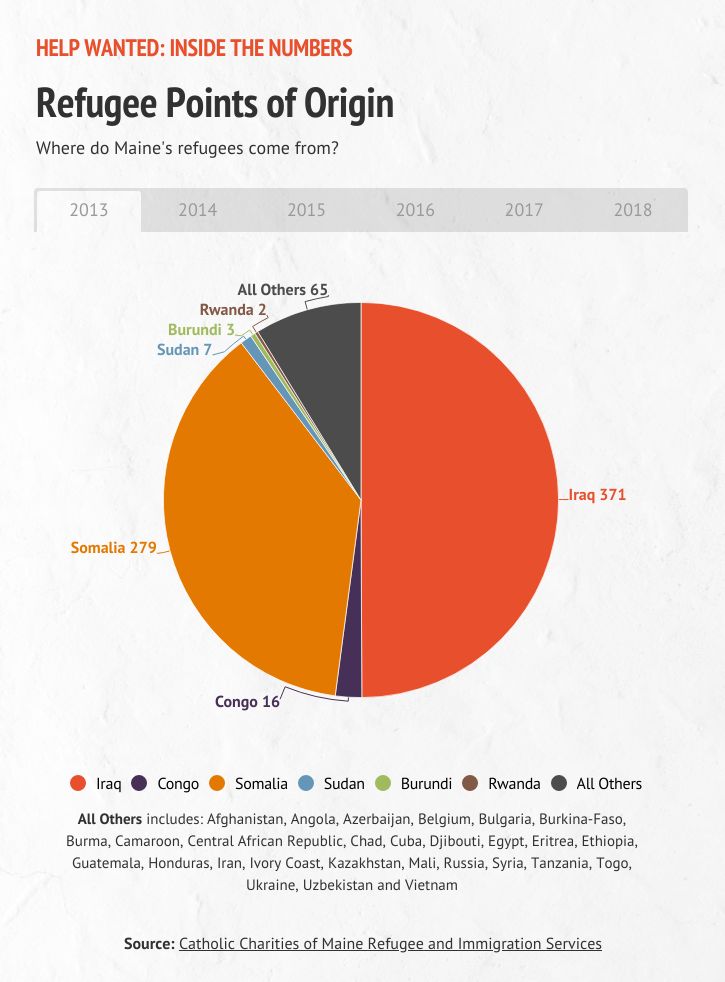

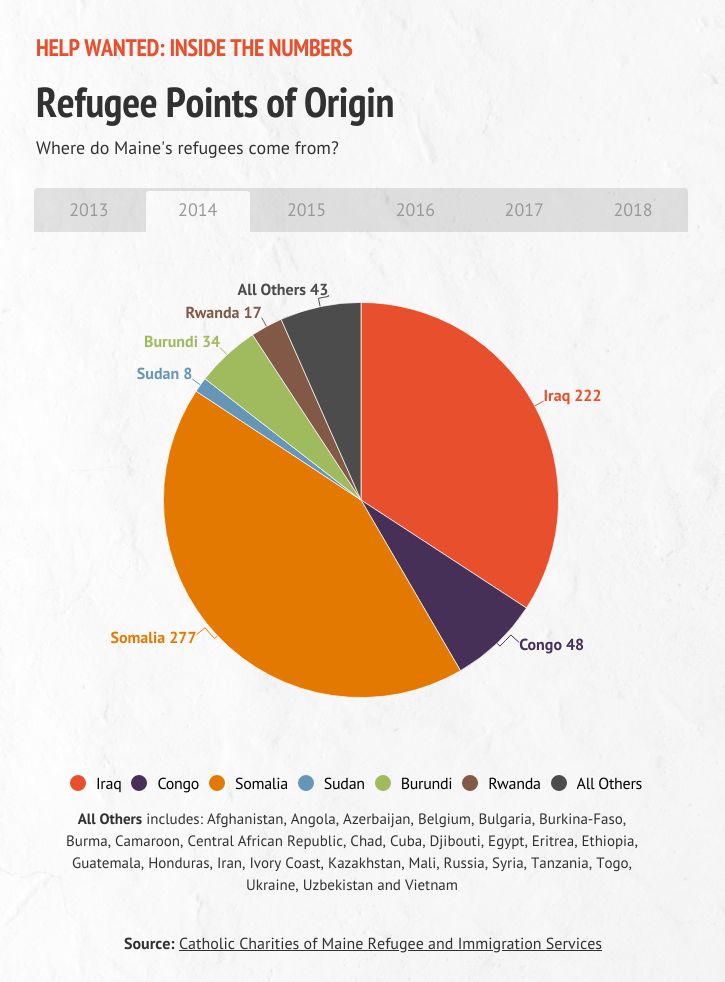

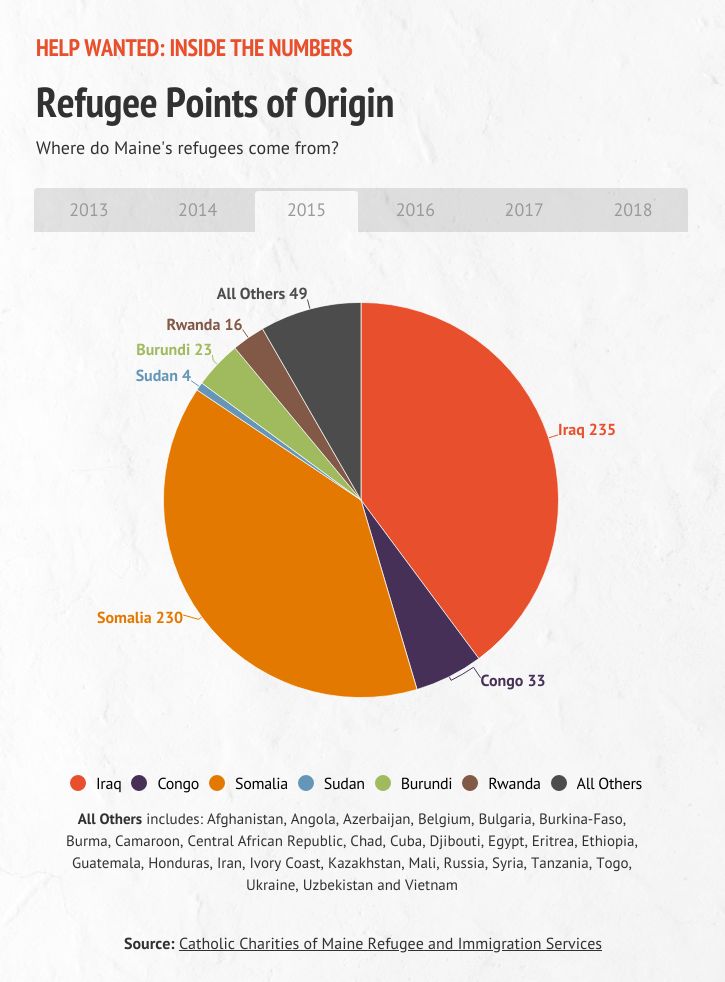

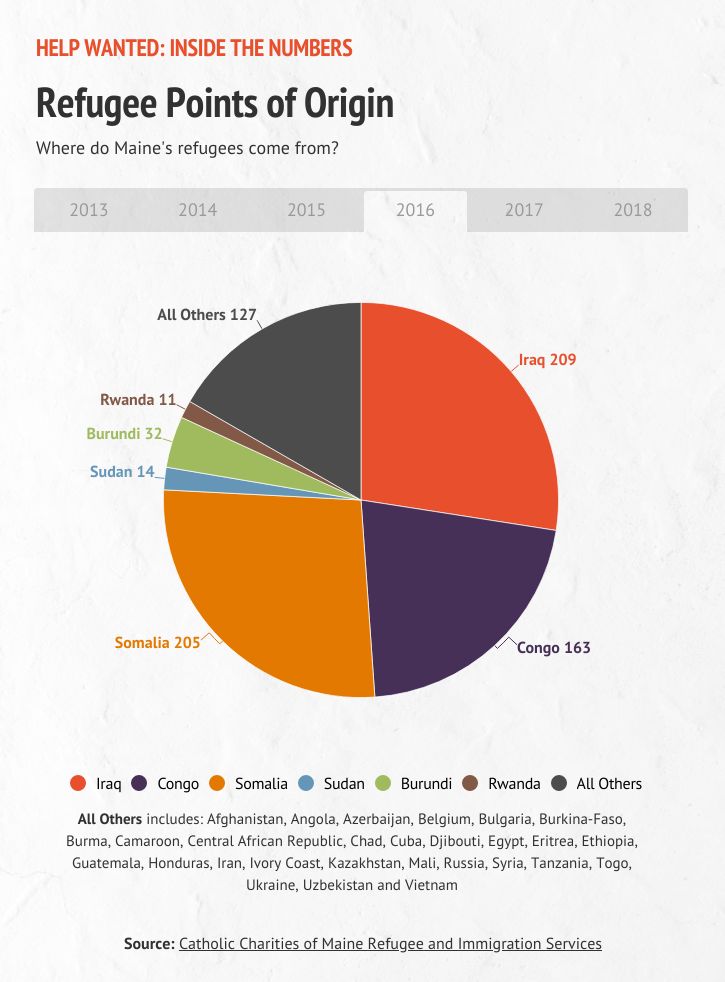

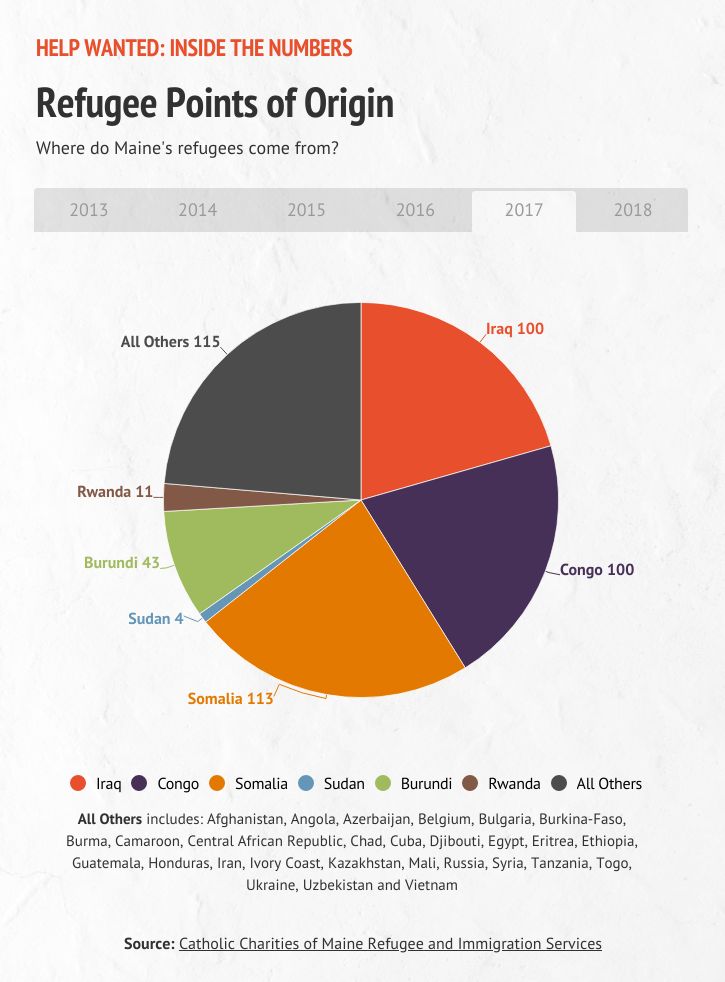

The yearly breakdown of refugees’ point of origin mirrors crises around the world. Influxes of refugees from Cambodia, the former Yugoslavia and Somalia have coincided with genocide, war and famine in those places. Recent arrivals include many people from Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola who were suffering from systemic instability and violence in their home countries.

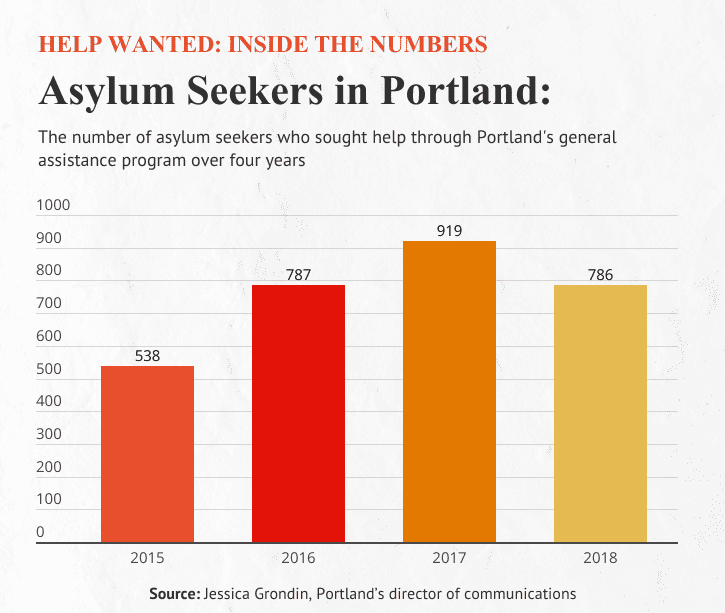

Gauging the number of asylum seekers and asylees is more difficult because there is no tracking mechanism other than where and when asylum seekers initially file their request. Local immigration experts say the best way to look for trends in Maine’s asylum-seeker population is to consider general assistance numbers for Portland, which tracks the number of asylum seekers in the program. Because asylum seekers cannot work for six months after filing, many turn to general assistance. Portland general assistance numbers reflect a growing population of asylum seekers.

In addition to cutting back on the number of refugees, the Trump administration is aggressively working to reduce the number of asylum seekers in the United States. At the time of publication, the administration had just announced plans to charge processing fees for asylum applications, deny work permits to asylum seekers who are in the United States illegally and fast-track asylum hearings.

Because federal policy has cut the rate of legal immigration, states interested in growing populations and workforces are increasingly focusing on attracting secondary migrants and asylum seekers. Roger Katz, a former Republican state senator from Augusta who has advocated for increasing state support for immigrants attempting to enter the Maine workforce, notes that Maine has some advantages in reaching the population of secondary migrants.

“It’s about people who are already here in this country and who are looking to make their lives,” says Katz, who termed out of the Maine Senate in 2018. “In Maine, we have certain things going for us. We are a very low-crime state. I think Maine people, once they get to know them, are welcoming, and we believe in community in our towns and cities. The biggest ambassadors we can have, are (the immigrants) who are already here.”

(While not the main target of workforce recruitment efforts, employees with temporary work visas also play a role in Maine’s economies. These include workers who are temporarily allowed to work in the U.S. through visas such as the H2-B visa for seasonal employment (a mainstay for Maine’s seasonal hospitality industry), and the H1-B visa for “specialty occupations” such as scientific researchers who play a key role in places like Bar Harbor’s Jackson Laboratory.)

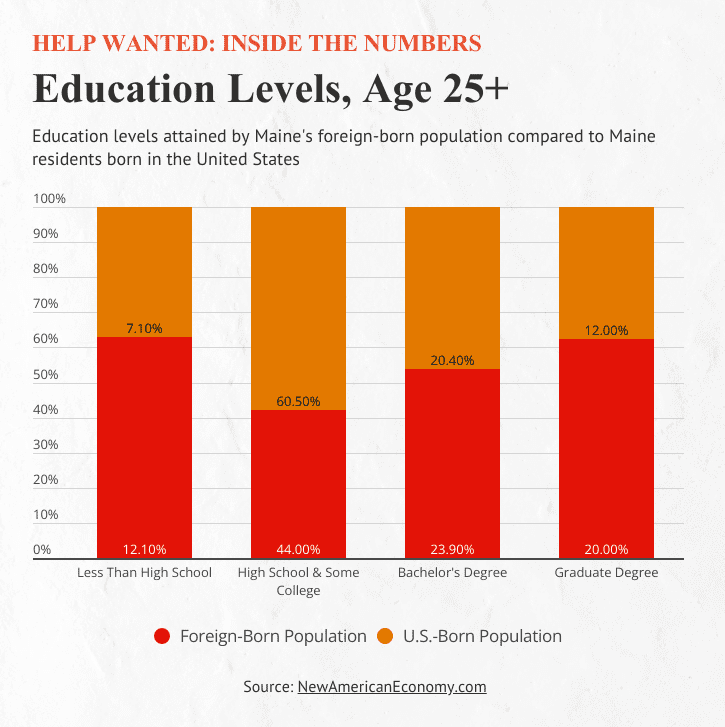

Advocates of helping immigrants enter Maine’s workforce point to the fact that immigrants have a higher rate of professional education than U.S.-born Mainers. This education edge is especially true for asylum seekers, who typically finance their own way to the United States and are more likely to have worked in professional jobs in their home countries than refugees, many of whom have spent years in refugee camps and have less work experience.

“Our refugee clients are coming from refugee camps, and have often been there for decades,” says DeAngelis of Catholic Charities Maine. “We are often working with people who have had very limited work experience because they haven’t had options to work. That’s different from asylum seekers. Asylum seekers have had to come here by their own means, somehow.”

These different education levels are reflected in the demographics of foreign-born Mainers, according to data from the New American Economy, a national nonprofit that advocates for immigration public policy that “grows economies and creates jobs.”

In Maine, 13.6 percent of the foreign-born population did not finish high school, compared with 7.2 percent of the native-born population. On the other hand, 21.6 percent of the foreign-born population have bachelor’s degrees, compared with 19.1 percent of the native population.

As far as age demographics, the foreign-born population tends to be slightly older than the native-born population, with a median age of 46.5 compared with the state’s median age of 44.2 for the U.S.-born population, according to the Migration Policy Institute.

Businesses tapping into immigrant labor pool

For Maine businesses, the data cited by economists is reflected in day-to-day operations, and these businesses are reacting to their workforce challenges by turning to immigrants.

“You can see the situation for yourself. Just drive around and look at the number of ‘We’re Hiring’ signs out there,” says Katz, who co-sponsored LD 1492, a 2018 bill (which failed to make it out of the Appropriations Committee) that would have provided support such as increased English language learning resources for immigrants in the workplace. “It’s literally hitting everybody in the face every day. People don’t put those ‘Help Wanted’ signs out unless they are desperate. A lot of this shows in the data that people like me look at long before it hits the streets. But now that it has hit the streets, everybody can see it.”

In fact, many Maine companies already are heavily dependent on immigrant workers. Without them, company managers say they couldn’t meet current workforce needs or expand.

For example, Ready Seafood, one of Maine’s largest lobster-processing companies, now has a workforce of more than 200 in Portland and Scarborough that’s more than half foreign born. Faced with a scarcity of new workers from traditional help-wanted postings, the company has found success by recruiting immigrants.

“About three years ago, there was really a big shift in the employment market,” says CEO Brian Skoczenski. “There was a combination of things that led to the shortage of workers, including drug use. It really opened up our eyes that we needed to look in different directions for employment. Before, when we posted on Craigslist, we would get one or two people in here. But that kind of went away, and we started to get one or no responses. It made us rethink how we were staffing. I reached out to the city of Portland, and they got me in touch with the general assistance program. The first time I asked for a couple of people to see how it would work. The next time they brought in around 27 (immigrants). That was an eye opener for us.”

Ready Seafood has now developed a pipeline for new workers, making the time-consuming task of recruitment easier.

“The pipeline (to potential immigrant workers) is organic,” says Skoczenski. “We haven’t posted a job for over a year. Every time we have an opening, an immigrant employee comes to us and asks if so-and-so can come in and interview. It has allowed us to concentrate on growing our business rather than making sure the day-to-day is getting done.”

Ben Waxman, co-owner of American Roots, the Westbrook clothing manufacturer, echoes Skoczenski’s comment about the importance of immigrants to his company’s survival.

“Without the immigrant workforce there is no company, there’s no revenue,” says Waxman, who has 24 employees and plans to expand.

Maine businesses aren’t alone in accessing the immigrant workforce. All of northern New England’s workforce is aging.

“Businesses now know that we are in competition with other states because every state is aging,” says the Maine Business Immigration Coalition’s Stickney. “At the national level both the economist community and the mainstream business community are aware that there is an absolute crisis in our workforce. In Maine, we’re pretty famous for saying we are the oldest state in the nation, but the reality is that other states are only a year or two behind us in terms of the median age. The whole country is graying. The birth rate is down for the entire country, and the unemployment rate is low. So, you have companies that want to grow, but where are we going to get our talent?”

To make it easier for businesses to connect with immigrants and to help coordinate services, the city of Portland created the Portland Office of Economic Opportunity in 2017. Run by Julia Trujillo, its mission is to help integrate immigrants into the economy so that businesses can connect with potential employees.

Skoczenski points to the office as the source of Ready Seafood’s recruitment success: “Julia is the only reason this program is working for us. She is the driving force. She reached out (to potential workers) and literally the next day it was like an on switch (for applications).”

Trujillo says part of her role is to identify gaps and to help organizations “work collectively better,” making Portland an attractive landing place for immigrants who want to work and for businesses who want to hire them.

“It shocked me that many other states (like Kentucky) are fighting for the same workforce,” says Trujillo. “Kentucky is putting a great effort into immigrant integration to make sure they are retaining everyone in their state and also attracting others to their state – targeting secondary migrants (immigrants who initially settled everywhere). Many states are fighting for these people. That’s why it’s so important to get this right and show advantages beyond our quality of life.”

Despite a need for employees, employers are sometimes hesitant to turn to the immigrant community because of a lack of knowledge about this pool of workers and fear that taking on a foreign-born workforce will be too complicated.

Skoczenski sees Trujillo’s office as an example of how city and state organizations can reduce such employer concerns and make the hiring process more attractive.

“Businesses use the resources that are already there,” says Skoczenski. “(Hiring immigrants) is an extremely overwhelming idea because of the unknown. Small business gets so bogged down and stretched so thin. We need to make it easier for them and to help them understand. There needs to be more outreach to business. Unless it is easy, businesses aren’t going to do it, and unless they see the benefits, they aren’t going to do it.”

The Maine State Chamber of Commerce has become a leading voice in supporting an increased role for immigrants in the workforce – a direction that diverges from current Trump administration policies toward reducing legal immigration to the United States and making the process of employing foreign workers more onerous.

“Immigrants can play a significant role in addressing Maine’s workforce challenge,” says Dana Connors, president of the chamber. “Maine’s history makes the case for the importance and impact of immigrants on this state.”

Connors notes that discussions about “legal” immigrants in the workforce often are derailed by the polarizing national debates over immigrants who are in the country illegally.

“Polarization brings confusion to the issues,” he says. “DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) and other efforts (involving issues surrounding immigrants who are in the country illegally) add more confusion. It’s contradictory to what we know (about the importance of legal immigrants in the workforce.) There are enough barriers now – the polarization doesn’t help.”

Overcoming these barriers are at the core of efforts to connect Maine employers with an underused labor pool.