Black Mainers are less likely to own a business than white residents, and those who do report earning substantially less money than white peers, according to publicly available data.

While this is consistent with national trends, a lack of detailed, up-to-date statistics hampers deep, state-level analysis. Researchers and advocates say more information is needed to understand the situation in Maine — and take steps to reduce disparities.

“The Census Bureau withholds a lot of the data for small groups, which unfortunately means not much data for Black communities,” said James Myall, a policy analyst at the Maine Center for Economic Policy.

The most recent Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs, published by the U.S. Census Bureau estimates there were 159 Black-owned businesses with paid employees in Maine in 2016, or just under eight business owners per 1,000 Black residents, said Myall. There were 22 business owners per 1,000 white, non-Hispanic Maine residents. This does not include businesses that lack employees.

In 2017, Black-owned businesses in Maine employed approximately 1,000 to 2,499 people. The Census Bureau has not released the number of Black-owned businesses from its 2017 survey because the number of responses was too small.

Data for 2018 is set to be published “within the next few months,” according to a spokesperson for the agency, though results could be suppressed for the same reason.

Black firm ownership and job creation appear to have grown in Maine from 2012, when 58 Black-owned companies employed a total of 500 to 1,000 people. Despite being eight years old, the 2012 Survey of Business Owners remains Maine’s most comprehensive source on Black business ownership, Myall said. It is the only business survey that reveals the total revenue Black-owned firms brought in — about $110 million that year.

It also estimated there were 858 Black-owned businesses without multiple employees in 2012. A smaller but more recent survey, the American Community Survey, estimated Maine had 618 Black owners of businesses — with employees and without — in 2018. This equates to 5 percent of Maine’s working-age Black population owning a business, compared to 13 percent of working-age white residents.

RELATED: Online directory aims to help Black businesses thrive in nation’s whitest state

The Survey of Business Owners was replaced with a new Annual Business Survey before an updated version was due in 2017. Myall said the replacement might be expanded to collect large enough sample sizes to release comparable racial data to the 2012 survey, but “that’s usually a matter of funding levels and priority-setting.

“In theory, we should be able to pool together several years of data collection to get a better sample once it’s been going for a while,” he added. “However, in practice the Census Bureau doesn’t always publish those multi-year estimates so it won’t necessarily be available.”

The lag time between when the Census Bureau collects and releases economic data makes it difficult to monitor trends or measure the immediate impacts of initiatives like the Black Owned Maine online directory, which launched this spring, and has raised public awareness and financial support for Black businesses in the state.

Maine’s Black population also grew by 2.9 percent in 2018, and a wave of immigrants and asylum-seekers — primarily from the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Angola — moved to the state the following year.

This shift has not yet been reflected in the Census surveys, and other economic reports are outdated or do not separate immigrant communities by race. Only 20 percent of Maine immigrants are born in Africa, according to the Migration Policy Institute.

“Data is important to actually highlight the impact of Maine immigrant-owned, Black-owned businesses,” said Claude Rwaganje, who has been frustrated by the absence of adequate metrics. Rwaganje is the executive director of ProsperityME, a Portland-based nonprofit that helps immigrants and refugees achieve financial stability.

Data is important to actually highlight the impact of Maine immigrant-owned, Black-owned businesses.”

— Claude Rwaganje, executive director of ProsperityME

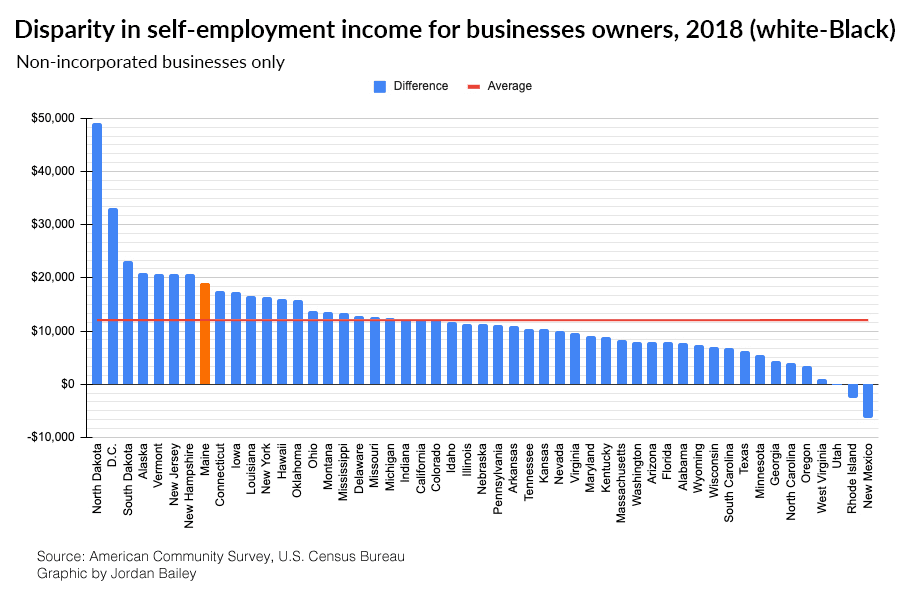

Income disparities are similarly difficult to gauge in Maine, but other census data indicates it is higher than most states.

The difference in average annual self-employment income between Black and white Maine residents who reported owning their own, active businesses was nearly $20,000 in 2018 — $11,831 for Black Mainers and $30,878 for white Mainers — according to estimates from the Census’ latest American Community Survey (ACS) Public Use microdata.

The income gap is also evident across most states, with Maine showing the eighth-highest disparity in the country. The mean difference between self-employment income for Black and white business owners nationally was $12,000 in 2018, according to the ACS.

Business owners can have other sources of income, but the average overall income for white business owners is still estimated to be about $10,000 higher than for Black Mainers, according to the survey.

The American Community Survey datasets are based on smaller sample sizes than the business surveys, but are less suppressed than the agency’s other reports, according to a Census spokesperson. The 2018 ACS estimates that The Maine Monitor used are based on five years of surveys, each reaching about 3.5 million households nationally, or roughly 1 percent of the population.

Our comparisons reflect only non-incorporated businesses — which are typically sole proprietor or partnership companies — that reported profits or losses. Estimates of self-employment income for Black owners of incorporated businesses are suppressed in the data for several states, including Maine, because of small sample size. (The raw survey data shows that only two of the Black respondents to the 2018 survey reported owning incorporated businesses, though it estimated 90 incorporated Black-owned businesses existed that year.)

Maine’s Secretary of State office maintains the state’s registry of corporations, but does not collect information on race, so it cannot provide an exact number of Black-owned, incorporated businesses or any information on their earnings.

Ryan Wallace, director of the Maine Center for Business and Economic Research at the University of Southern Maine’s Muskie School of Public Service, said while the American Community Survey provides useful information on race and business ownership, there are several caveats.

“Number one, you’ve got to be careful with sample sizes because they aren’t exactly significant numbers in the first place,” he said. “We’re the whitest state in the country and so when you start getting down to the sampling of that, there’s just a bit more room for sampling error.”

Small states like Rhode Island — one of the three states where Black self-employment income among business owners was estimated to be higher than white self-employment income — may also have high sampling error, he said.

Business owners may supplement their income with other forms of self-employment, such as driving for Uber or Lyft, Wallace said. The ACS does not separate self-employment income by source, so it is difficult to determine how much money a person earned from gig work versus their own business. To address this, The Maine Monitor filtered the self-employment income estimates to include only those who own active businesses. Without that filter, Black residents had an estimated average of $9,150 in self employment income in 2018 compared to $26,210 for white residents. That disparity raises additional questions.

“What type of jobs are they doing comparatively?” Wallace asked. “Are there differences in gig work between groups?”

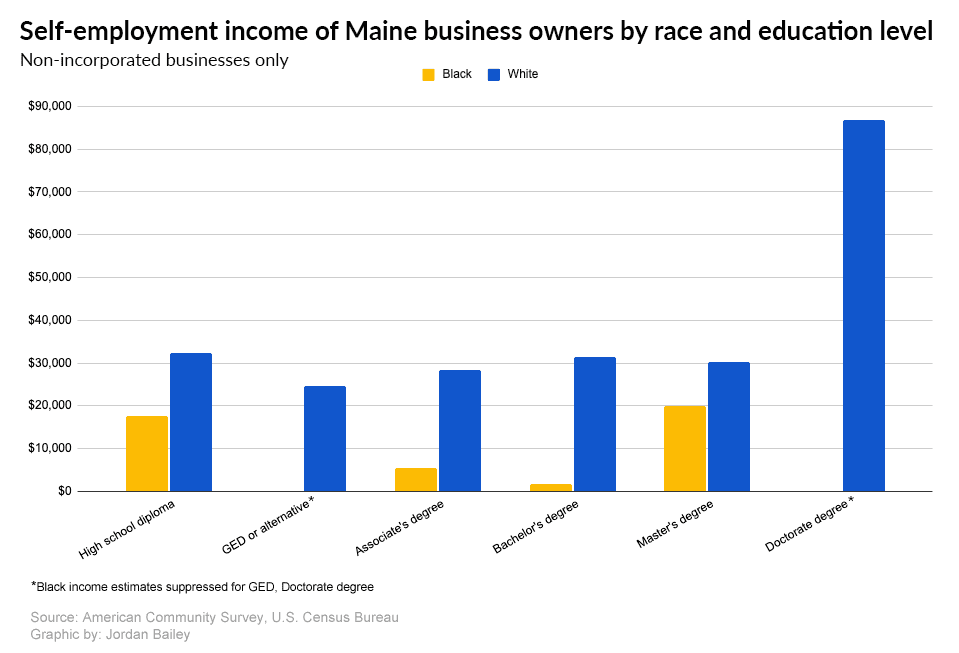

Wallace also warned against drawing too many conclusions from these comparisons without factoring in industry, occupation, age and education, which he said are all important in explaining differences in self-employment income.

When people who are seasoned in an industry — typically entrepreneurs over 50 — develop a new venture in that sector, for instance, they bring in higher incomes due to their expertise in the field.

White entrepreneurs typically have more access to capital, with more personal assets and the ability to raise seed funding from family and friends, than Black entrepreneurs, Wallace said. This can affect the kinds of businesses Black entrepreneurs can pursue — and the earnings they make.

They might not have the infrastructure to collect the data that’s needed. That’s where the state comes in, that’s where other stakeholders around the state should come in, to help build that infrastructure … to help impacted communities identify what the solutions should be.”

— Joby Thoyalil, member of the Permanent Commission on the Status of Racial, Indigenous and Maine Tribal Populations

Nationally, these factors have played a role. Robert Fairlie, an economist at the University of California at Santa Cruz, has studied minority business ownership for decades. In an analysis of the American Community Survey microdata for 2011-15, he found that lower business ownership rates among Black people can be attributed to low levels of wealth, and to being relatively younger than white entrepreneurs.

He also found that lower levels of education contribute to why Black Americans have lower business income. A study he did in 2016 found that Black-owned startups had difficulty raising capital, that they do not catch up over time, and that racial bias in lending plays a partial role in the disparity.

In his latest paper, an analysis of the impacts of the pandemic on minority businesses, he found that the country lost nearly 450,000 active African-American business owners from February through April, or 41 percent, while Latinx businesses dropped 32 percent and immigrant businesses dropped 36 percent.

“We already have disparities. African-Americans have the lowest business-ownership rate in the population,” he told the Washington Post. “And so here we’re creating a situation of closures that’s hitting the groups with the lowest rates even harder.”

The Maine ACS self-employment income estimates could not be broken down by industry or age, but estimates were provided for different education levels. They show racial disparities persist for business owners with the same education level. While no estimate was provided for self-employment income of Black business owners with doctorate degrees, the high income of white business owners in that category might explain some of Maine’s $20,000 disparity.

More research is needed to fully understand the extent and causes of Maine’s disparity in self-employment income between Black and white residents.

The Permanent Commission on the Status of Racial, Indigenous and Maine Tribal Populations — established by the Legislature in 2019 — has been charged with identifying where data gaps lie, said Commissioner Joby Thoyalil, a senior policy advocate at Maine Equal Justice. State agencies will also need a mandate to adequately measure and track disparities, according to the commission’s recommendations to the Legislature, which were published in September.

Collecting the missing data will take investment, Thoyalil said, but is essential to eliminating racial disparities, as is involving communities that are most impacted.

“The best solutions are going to come from them,” Thoyalil said during an online panel discussion Sept. 16. “They’re the ones with the experience, they’re the ones with the most expertise … They might not have the infrastructure to collect the data that’s needed. That’s where the state comes in, that’s where other stakeholders around the state should come in, to help build that infrastructure … to help impacted communities identify what the solutions should be.”