LEWISTON — Hibo Omer’s campaign against lead poisoning began nearly two decades ago. When she brought her 8-month-old and 3-year-old to a doctor for a routine checkup, she was asked what she thought was a bizarre question: the age of her rental home.

“I’m like, ‘How on Earth would I know?’ ” Omer said.

When nurses learned the home was built before lead-based paint was banned in 1978, they tested her children for lead poisoning, a buildup of the heavy metal in the body that can damage the brain and nervous system of young children.

The sudden hyperactivity in Omer’s young son began to make sense. Young children are the most vulnerable to lead exposure because they may inhale lead dust while crawling around or put their mouths on peeling painted wood such as window sills. And their brains can more easily absorb the lead. Experts say no level of the substance is safe for children.

Lead poisoning has been linked to developmental delays, behavioral problems, poorer school performance and lower earnings. State officials say the “overwhelming” majority of cases in Maine occur in homes built around or before 1950, particularly those that fell into disrepair, because the lead becomes most dangerous as the paint chips and crumbles.

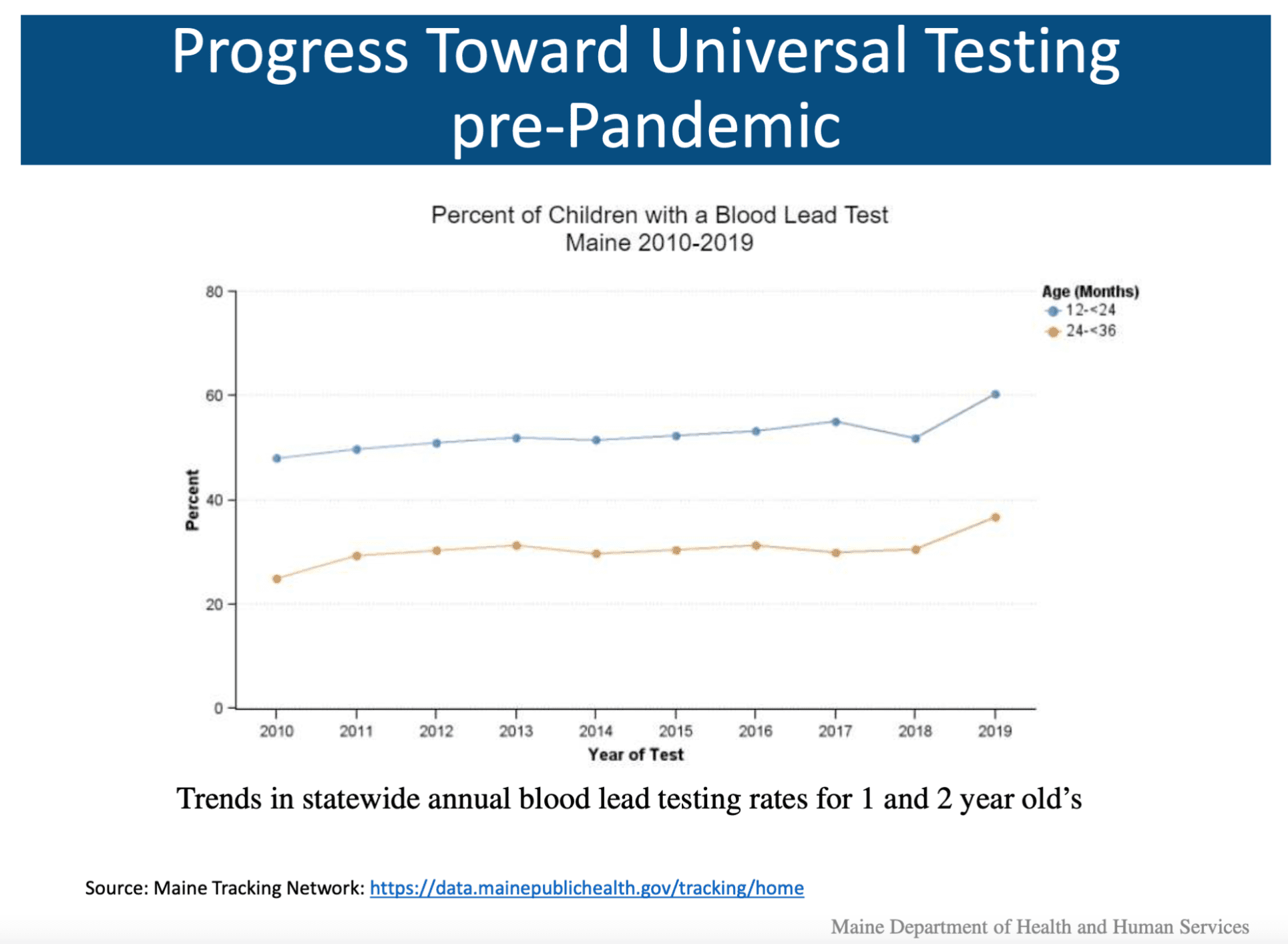

After capturing nationwide attention in the 1970s and ‘80s, Maine experts say, lead poisoning was overshadowed by other public health crises in later decades. That seems to be changing. In recent years, Maine lowered the lead poisoning threshold and increased testing in young children. Prior to 2015, the definition of lead poisoning was a blood lead level of 15 micrograms per deciliter. That level was lowered to 5.

And last month, Lewiston received a $30 million federal grant to redevelop and construct 185 units in a neighborhood with a high concentration of childhood lead poisoning.

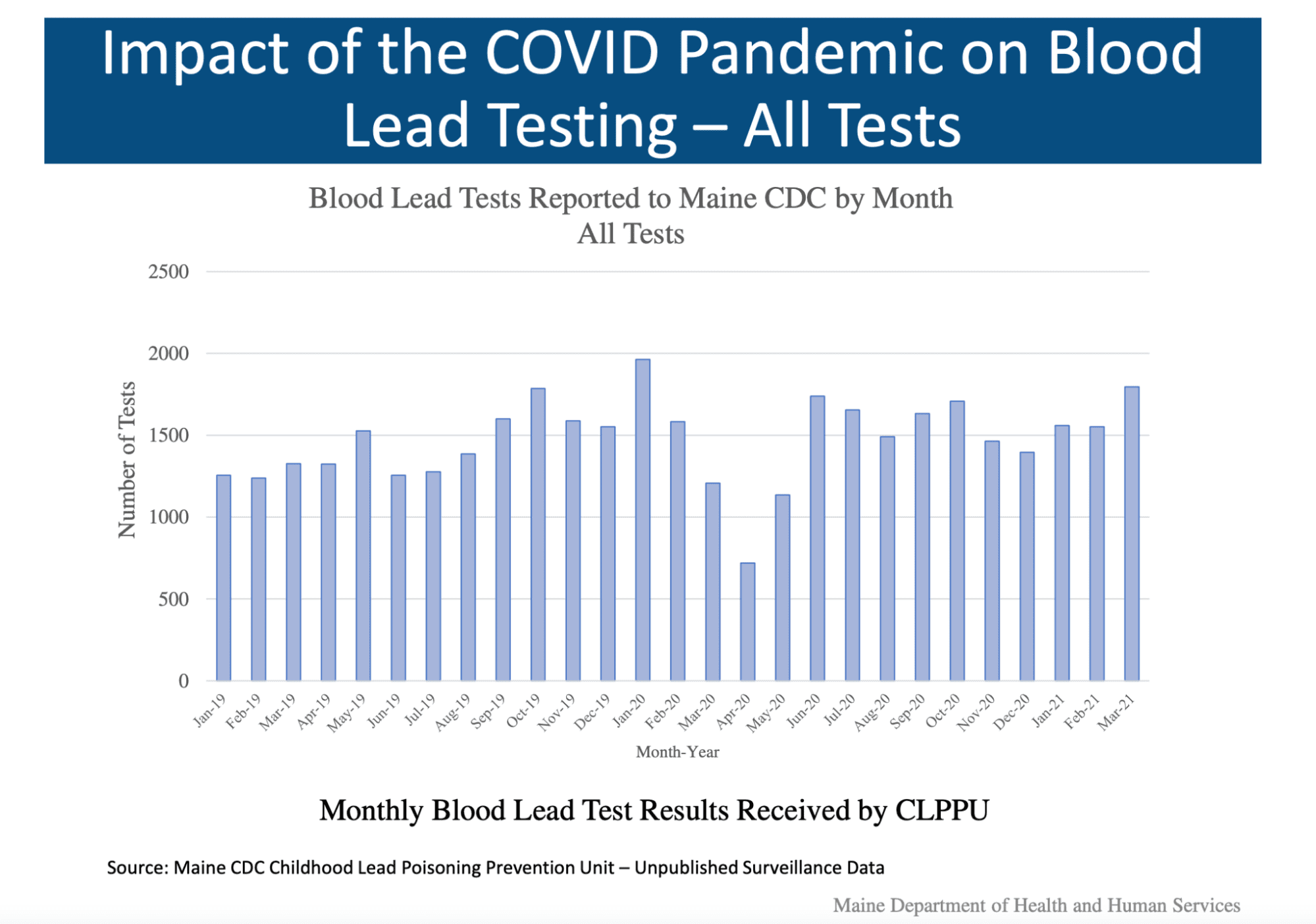

Data suggests these efforts were ramping up before the COVID-19 pandemic brought the world to a standstill in the spring of 2020. Recently, as the state started opening up, officials saw the momentum to combat lead poisoning pick up again, with rebounding test rates and increased attention from the White House. Still, activists say the progress is insufficient.

RELATED: The problem for Maine kids that won’t go away: lead paint poisoning

For Omer, the problem has piqued her curiosity. After her initial introduction to lead poisoning, she looked for opportunities to study the neurological impacts of lead exposure while pursuing her master’s and now her doctorate degree. She also serves as program director with the New Mainers Public Health Initiative.

One question kept nagging her: Why does a wealthy country like the U.S. allow people to live in contaminated homes?

Growing up in Ethiopia, she would have found the idea absurd.

“If you come to Ethiopia with me and if I tell you the home you’re living in is poisonous, you will think, ‘How could this happen?’ ” Omer said.

Living with lead

When a Lewiston woman, using Omer as a translator, brought her 3-day-old baby back to her rental house in Lewiston, she didn’t know she was endangering her child.

Shortly after she moved in with her five children, the youngest ones developed behavioral problems and could no longer sleep through the night.

“The kids became extra hyper, as if they’re just crazy,” she said in Somali.

Even after her children developed health problems, she didn’t speak up out of fear she would lose her immigration status or be blacklisted from renting another home.

They had just moved from Somalia to Maine. She didn’t have a job, didn’t speak English and didn’t have the savings for a deposit on a different rental. They remained in the hazardous home for a year before moving into a low-income housing unit.

“There were so many layers of fear that I had. And that fear, I kept it to myself,” she said. She asked to remain anonymous because she still lives with that fear, nearly five years after moving out of the home.

The woman and her children also visited emergency rooms numerous times for severe rashes they developed while living in that home, and the youngest child has since been diagnosed with autism. However, The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention do not list rashes or autism as health effects from lead poisoning.

Years later, she feels angry at herself for staying in the home for as long as she did and not saying anything sooner. If she were in the situation again, she would speak up.

“Now, I became an American. I wouldn’t take that,” Omer translated, as they both laughed. She added more seriously: “I’m brave now.”

A history of lead challenges

Lewiston-Auburn, which has struggled with high rates of lead poisoning for years, recorded the state’s highest case count in 2019, the most recent available data.

It had 36 confirmed and estimated cases of lead poisoning in 2019, or 12.3% of the state’s 292 estimated cases that year. Portland-Westbrook had 35 cases and Saco-Biddeford had 19.

State officials said they are compiling data from 2020, which will be released later this summer.

About 40% of childhood lead poisoning cases in Maine are found in Lewiston-Auburn, Portland-Westbrook, Bangor, Saco-Biddeford and Sanford, according to the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention. And within those areas, the vast majority of cases involved children in rental housing.

While the estimated percentage of lead-poisoned 1- and 2-year-olds in Lewiston-Auburn fell markedly from 2010 to 2019, its rate of 4% remained higher than the state’s rate of 2.3%.

Lewiston’s old and distressed housing stock is concentrated downtown, where a third of the city’s youth live. That creates a “perfect storm” for high rates of childhood lead poisoning, said Misty Parker, Lewiston’s economic development manager.

RELATED: Lewiston-Auburn ground zero in war against lead poisoning of kids

The city has received funding for lead remediation programs over the years, Parker said, but it became clear the efforts were a “Band Aid on the real problem” of aging housing. The city needed a bolder approach to reach its goal of a lead-free downtown by 2043.

Last month, after an application process that began three years ago, Lewiston was awarded a $30 million grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to replace 92 existing housing units, and build 93 new workforce and unrestricted units in the downtown Tree Streets neighborhood. About 30% of the grant will support community programs that expand access to child care, pediatric health, community mentors, youth programming and affordable food, Parker said.

The city is grateful for the funds, Parker said, but the grant won’t fully solve the lead problem. It’s expected to take 24 years for Lewiston to reach its “hefty goal” of replacing all 1,451 of its pre-1950 dwelling units in the Tree Streets area.

Still, Parker said she hopes the grant and the state’s recent efforts to increase testing will keep the focus on lead poisoning.

“It is a problem that should have been dealt with a long time ago, and unfortunately it wasn’t,” she said. “It’s our responsibility now to fix it. We owe it to these kids. They’re the future of our community. And we need to do everything we can to give them the best shot.”

In addition to the old and dense housing stock in Lewiston, there could be other factors, said Rebecca Boulos, executive director of the Maine Public Health Association. Lewiston has a large immigrant community from Central and East Africa, and lead poisoning has been shown to disproportionately impact children of color.

Like other national public health problems, the explanation for this disparity isn’t biological, Boulos said. Rather, systems that are in place push non-white people into lower-quality housing and allow landlords to ignore problems.

“I think part of the problem is that there is racism in housing, there’s racism in zoning, and the reality is, for a lot of these families, they’re living in places that are probably not very healthy,” Boulos said.

Maine collects data on race and ethnicity for lead poisoning cases, but does not release it publicly because more than 40% of the responses are missing or incomplete. As a result, data could be misleading, said Andrew Smith, state toxicologist with the Maine CDC.

But the state is working on integrating lead poisoning data with birth and immunization records — which received more attention during COVID-19 — to better understand whether there is a disproportionate impact on Mainers of color.

Addressing lead poisoning will come down to political will and capacity, Boulos said. For the state to be proactive, it needs more people who can conduct testing in homes and enforce safety regulations.

“The state needs more public health workers,” Boulos said. “The action step is we need more people working, period. In public health we need them addressing lead, we need them addressing radon and we need them addressing water (quality).”

Abatement cost ‘paralysis’

On a blustery day last April, Hibo Omer peered into an abandoned house on Maple Street in Lewiston. From the outside, the house looked like the rest on its block. But a single piece of paper taped to the front window declared it hazardous. And on the other side of the glass windows, a staircase was littered with pieces of crumbling ceiling.

The house is one of many in the state with lingering lead problems despite the lead paint ban in 1978.

It is not illegal to have lead paint in a home. But if a resident is exposed to crumbling paint chips and gets sick, the landlord could be ordered to remove or safely cover the lead before renting to new tenants.

Mahdi Irobe, the owner, said he knew he could have tested the building for lead before buying it, but thought lead exposure was a small problem he could fix on his own.

The state offers free, do-it-yourself lead test kits that are targeted toward homes built before 1950.

A few months after Irobe purchased the home, one of his tenants got sick. The city performed an inspection and found lead. All the tenants in the three units had to move and the house has sat empty for a year. Irobe paid $150,000 for the home, and said he paid $1,500 in property taxes last year on the empty dwelling.

The tenants found other places to live. The home remains empty because, Irobe says, he can’t afford to remove the lead.

“I cannot rent the place that has the lead,” he said. “As you can see, I’m losing a lot of money on my building every month and it’s just empty.”

Irobe, who also owns and operates a MoneyGram business on Lisbon Street in Lewiston, said he knows other landlords who have dealt with lead problems longer than he has. He said he doesn’t know where to turn next.

Housing officials agree that the cost of removing lead can render people “paralyzed.” There are grant programs to help property owners, but they help a relatively small number of units a year.

Lewiston, Biddeford and Cumberland County operate their own lead-abatement programs and MaineHousing, the state’s housing authority, runs the program for the rest of the state. To be eligible, homeowners must fall below an income requirement, and property owners must rent to tenants below an income requirement.

Lewiston officials say funds are available in the city’s lead abatement program for property owners, but they must follow a formal bidding process and use vetted contractors. Property owners cannot receive the money directly to do the work themselves. The city’s program abates an average of 75 units a year.

In 2020, MaineHousing abated 145 units through its program — down from 232 in 2019. Spokeswoman Cara Courchesne said the pandemic likely deterred people from applying for the program.

Maine’s housing stock is the eighth-oldest in the country. More than 313,000 units in the state could date before 1978, according to the latest census. It’s unclear how many have been scrubbed of lead through various programs or private contracts, Courchesne said.

MaineHousing received about $5 million in state and federal funds for the current grant cycle from February 2020 through August 2023. It cost, on average, a little more than $13,300 per unit to abate lead in 2020.

The problem is frustrating, Courchesne said, because it’s solvable: The number of homes with lead paint isn’t growing, and there are known ways to remove lead. But it’s an expensive process, and there’s been a backlog in available contractors licensed for lead removal.

Nonetheless, Maine is “trending in the right direction,” with more awareness statewide and increased coordination among agencies, she said.

“Like so many of the housing-related issues that we work on, this is a solvable problem that has an endpoint,” Courchesne said. “That’s something that tends to motivate people more, so we do feel hopeful.”

‘Cautiously optimistic’

Lead poisoning has proven difficult to solve in part because it received so much attention decades ago that people think it already has been fixed, Maine experts say. Successful legislative efforts in recent years, however, drummed up attention in Maine and have advocates hopeful that momentum is building.

Maine passed a law in 1990 to eradicate lead by 2010, but a 2015 investigation by The Maine Monitor found that thousands of children still were being poisoned five years after the deadline. That same year, Maine lowered the threshold for the amount of lead in the blood considered toxic in children, from 15 micrograms per deciliter to 5.

However, experts say no level of lead is safe in children.

From September 2019 to September 2020, four years after the law was changed, the state identified at least 1,166 additional poisoned children who would not have been detected at the previous threshold, said Greg Payne, director of the Maine Affordable Housing Coalition. That accounts for 90% of the total cases during that time period.

Maine also passed universal testing in 2019, requiring all children ages 1 and 2 be tested for lead exposure. Previously, Maine was the only New England state that had not mandated this testing for all children.

The Maine CDC hired eight additional environmental lead inspection coordinators and a public health nurse to implement the two legislative changes since 2015, said Andrew Smith, the state toxicologist.

The universal testing law went into effect in September 2019 and the numbers already were beginning to reflect a change that year. The percentage of 1-year-olds tested increased from 52% to 60% in 2019, according to the state.

“I think we were very pleased to see a jump so quickly,” Smith said. “But there’s no question we have a ways to go because we want to see these (rates) approaching 80% for both 1- and 2-year-olds.”

Some counties, such as Washington and Franklin, have reached or surpassed 80% testing rates for 1-year-olds, Smith said, so “it’s achievable” for other counties to do the same.

But the COVID-19 pandemic threw a wrench in some of that progress.

Testing rates continued to climb in early 2020, but dropped off when non-emergency services were paused due to the pandemic and parents were hesitant to bring their children in for care. Inspections, which are triggered by confirmed positive cases, dropped off as well.

Testing nationally also plummeted last spring. Some Midwestern states saw a 50% decrease from the prior year, Kaiser Health News reported.

Despite decreased testing, Maine was able to maintain its program and investigations throughout the pandemic while other state programs “largely went dormant,” Smith said.

Testing rates began to climb back up again in May and by March 2021 had surpassed rates before the universal testing law went into effect.

The policy change for universal testing already has changed practices on the ground, said Payne with the Maine Affordable Housing Coalition. Testing is “becoming a part of normal that it wasn’t before, and frankly we believe it should have before.”

Prior to universal testing, only children on MaineCare were required to be tested but the state fell far short of that goal. Only about half of those 1-year-olds and less than 37% of 2-year-olds were tested, according to the Maine Affordable Housing Coalition.

Payne said he is more optimistic about the state’s new universal testing requirement because state officials have been proactively working with pediatric offices to increase testing.

“I do believe that (Maine CDC employees) are energized by the results and are doing a great job with making sure that this works as intended,” Payne said. “And I do believe that we’ll continue to make progress.”

Some health systems, like Portland-based MaineHealth, are investing in technology that allows them to detect lead levels in-house, rather than having them sent to a lab, so doctors can talk to parents about their child’s results during the same visit. Those kinds of efforts make Payne feel optimistic that Maine will be able to streamline its testing efforts.

The state could look at other proactive measures such as requiring a lead test before selling a home and providing low-interest loans to make it more financially feasible for property owners to remove lead, Payne said. But also, over time, these houses will be culled from the housing stock as they get knocked down or renovated, which will help drive down cases.

Karyn Butts, manager for the Maine CDC Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Unit, said the state tries to prevent cases by mailing information about free test kits to all households with a 1-year-old, funding partners in the highest-risk areas to do local prevention and outreach, and training staff from programs that do in-home visits with young families so they can also recognize lead hazards and help the families conduct tests.

Butts said the state is making steady progress but it’s “house-by-house, year-by-year,” so the slow pace can be frustrating.

“The amount of investment it would take, either from the private property owner or in public investment, to remove lead from housing is happening, but it’s happening in an incremental way,” Butts said. “That’s slow progress, (but) we are making progress.”

Erin Guay, executive director of Healthy Androscoggin, a public health nonprofit based in Lewiston, said other cities across the country use a proactive approach with code enforcement officers performing inspections for lead before deeming a rental unit to be safe. But solutions like that will take resources and commitments from cities and towns.

“Often we’re dealing with whatever the crisis is at the moment, and we’re not as good at trying to prevent things down the line that are harder to measure and harder to see,” Guay said. “For instance, in Lewiston we have a full-time fire inspector, which is great, but we haven’t yet prioritized lead as an issue that deserves as much attention as people being displaced by fires.”

Some advocates say the state needs to move faster. Phelps Turner, a Maine-based attorney with the Conservation Law Foundation, said even if testing is increasing, “the more disturbing number is that hundreds of children every year continue to be poisoned by lead.”

Lead poisoning harms society’s most vulnerable, burdens families with extra healthcare costs and hinders the child’s future earning potential, Turner said. This creates an added strain going forward on both the healthcare system and the economy.

Solving the problem will require more funding from local, state and federal governments, but Turner said there may be other funding avenues as well. After a nearly 20-year legal battle in California, a judge ordered lead paint suppliers to pay $305 million to the state’s largest cities and counties.

Turner said the recent efforts in Maine and the Biden administration’s targeting of lead in water pipes could spur greater action.

“But there’s been a long history of inattention to this problem and insufficient funding for this problem at the state and federal level, so I guess I’m cautiously optimistic.”