The Penobscot tribal member looked out at the congregation, and the church’s red carpet and red upholstery.

The red carpeting and red upholstery, she explained, is a vivid symbol of her people’s blood.

The visiting guest speaker stunned several people sitting in Portland’s First Parish Church pews that Sunday morning.

“I was really startled,” said congregant Kristina Minister. “And I think everyone was.”

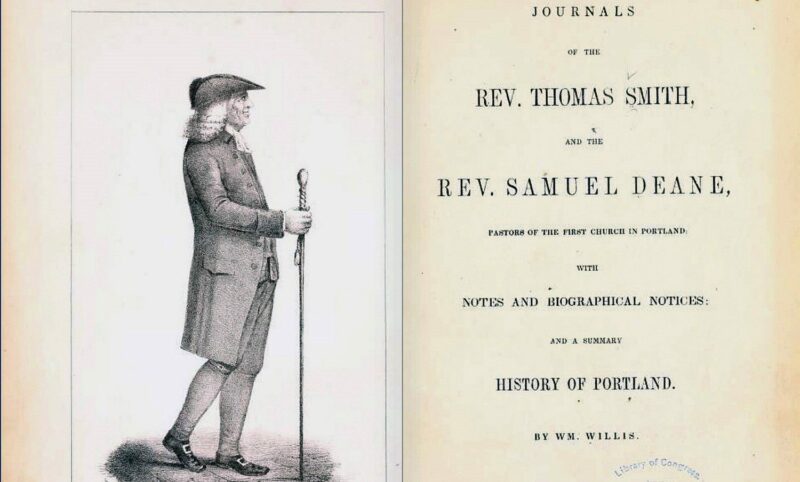

The Penobscot woman, who teaches about spiritual activism, explained that Rev. Thomas Smith, the Unitarian Universalist Church’s longest-serving minister, organized a posse to hunt, kill and scalp Wabanaki men, women and children to the east of Portland, or what was known as Falmouth in the 1700s.

Smith later wrote in his journal that he received 198 pounds, “my part in scalp money.”

The congregants, Minister remembered, fell silent while contemplating their church’s disturbing history. Several knew that Smith was the church’s pastor from 1727 until his death in 1795. Two plaques honoring Smith hung on the church walls.

“We all sort of knew about his past, his involvement with the scalping, but we didn’t own it,” said Minister. “It was history. Something in a book.”

Smith’s name reverberated in the historic meetinghouse as the Penobscot woman asked congregants to stand with her and acknowledge their past.

“She had us repeat the facts and that we object to this, and we wish to heal from it,” Minister said.

She also urged the congregation to make reparations, Minister said, for Smith’s blood money.

The reactions among church members were mixed. Some, Minister recalled, were in shock and disbelief. It was especially difficult to comprehend Smith’s actions in the Unitarian Universalist community, she said, which welcomes all faiths and abides by seven principles, including “the inherent worth and dignity of every person.”

Born in Boston and a Harvard graduate, Smith, they learned, also owned slaves.

Minister and Angus Ferguson, another First Parish Church member, agreed to research and write a “truth statement” that could be shared with the congregation about Smith’s role in the government-sanctioned genocide of Wabanaki people.

Smith, their research noted, responded to orders given by Massachusetts Bay Colony’s Lt. Gov. Spencer Phips to hunt and kill Wabanaki men, women and children. In a 1755 proclamation, Phips offered rewards for the Wabanaki scalps.

“Try as we may to rationalize or dismiss this history,” Ferguson and Minister wrote, “its solid legacy remains today right under our feet. This church stands on blooded land in an exploited, degraded environment — taken by genocide and terror for profit.”

RELATED: Generations later, Mainers confront a genocide that still remains overlooked

To make amends, the congregation formed a Wabanaki Alliance Team. It invited Wabanaki tribal members to lead workshops on how British colonial settlers forced Maine’s Indigenous people from their native land.

“They had a huge map of Maine that filled a whole room, and we stood on various parts of the state where the tribes lived,” Minister said. “And as the settlers came, we were pushed into three areas where the tribes now have their territories. It was a vivid example of how the settlers attempted genocide.”

The workshops, said Leslie Runser, co-chair of the church’s Wabanaki Alliance Team, were emotional and disturbing.

“It was absolutely brutal hearing what happened to the Wabanaki,” said Runser of the scalping expeditions and dispossessing Indigenous people of their homeland.

“I mourn for what my forebears did. I don’t have direct ancestors that were involved but I need to be the one to be responsible now. I need to be the one who says, ‘This isn’t right’ and to work to change the future.”

To make amends, Runser and other First Parish congregants collected food for Wabanaki elders. They’ve also advocated for Maine’s Indigenous people to self-govern like the 570 other federally recognized tribes across the country.

Currently the Wabanaki are bound by state laws under the 1980 Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act. The proposed ‘sovereignty bill’ would return privileges and power to the Wabanaki, allowing them to regulate what happens on tribal lands, including fishing, hunting, criminal offenses and collecting taxes.

Before each church service at First Parish, the congregation’s minister acknowledges that its meetinghouse stands on land seized from the Wabanaki “by genocidal violence that profited our forebearers.”

“Basically,” Minister said, “we’re saying we know we are on stolen land.”

The two plaques honoring Smith are also stark reminders of the church’s dark history.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, First Parish is Portland’s oldest place of worship. The church at 425 Congress St. was established in 1674 and its current granite building was completed in 1826.

A marble plaque in the church entryway notes Smith as part of the parish history. Smith is also listed on a 6-foot tall brass and wood plaque that hangs to the left of the pulpit.

“Every time I walk in there, I see those plaques and they’re right in my face, and it brings a lot of emotion,” said Meret Bainbridge, who co-chairs the church’s Wabanaki Alliance Team that meets each month.

Bainbridge can’t help but cry when thinking of the Wabanaki men, women and children who were hunted, murdered and scalped.

“Just the brutality and violence of it,” Bainbridge said. “That humans can do that to each other.”

Some congregants, Bainbridge said, have suggested the church cover the ornamental tablets.

“We could cover them up,” Bainbridge said, “but that would be just covering history and being in denial of it.”

Instead the church has agreed to create a permanent exhibit that explains how Smith organized a posse to murder the Wabanaki and profited from the scalping bounty.

Despite the uncomfortable emotions that Smith and the plaques stir, they remind Bainbridge of the commitments she and others must keep.

“The impulse might be to forget about this shameful piece of history,” Bainbridge said, “but we need to fulfill our promise to work toward truth-telling, education, healing and reconciliation.”

Update: An earlier version of this article misidentified the person addressing the congregation. She was a tribal member who was a guest speaker.

Reach Barbara Walsh by email: barbara@themainemonitor.org.