Editor’s Note: The following story first appeared in The Maine Monitor’s free environmental newsletter, Climate Monitor, that is delivered to inboxes for every Friday morning. Sign up for the free newsletter to get important environmental news by registering at this link.

Days after Hurricane Fiona slammed into Puerto Rico, many of the 3.2 million Americans who live there remain without power or clean water. The storm is the first to be named in what had so far been an abnormally quiet Atlantic hurricane season that is now heating up rapidly.

As of Thursday afternoon, Fiona was a Category 4 storm tracking toward Bermuda; after that, it’s forecast to swing wide up the East Coast before clobbering Nova Scotia with what’s increasingly expected to be unusual force.

“The upcoming landfall in eastern Nova Scotia on Saturday morning is still expected to be historic,” hurricane researcher Brian McNoldy wrote on his blog Thursday. “[T]he storm could break all-time record-low surface pressure values there, and with forecast sustained winds of 90 mph, it will also be one of the most intense storms that area has ever seen.”

Maine should be mostly in the clear, but can expect major swells, dangerous rip currents and strong northwesterly winds that could cause power outages as the storm passes by, pumped up by warmer-than-average sea temperatures.

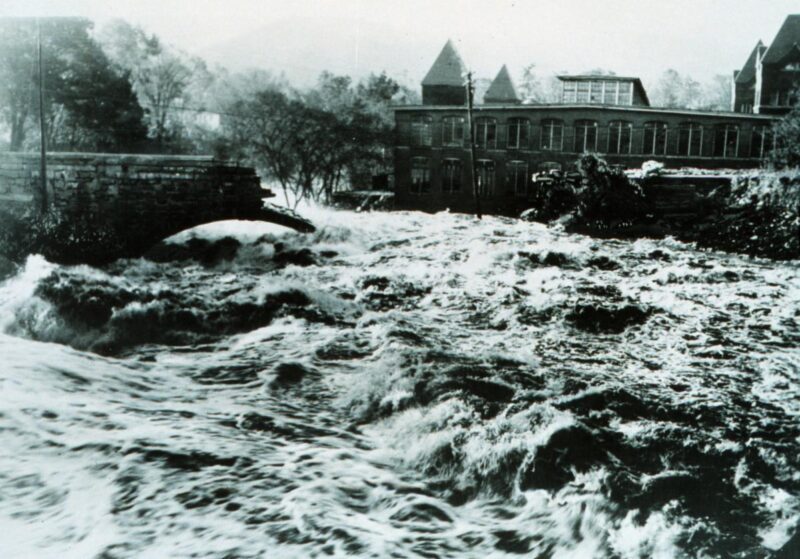

We know New England gets its share of hurricanes. Mainers will remember impacts from Sandy, Irene and Bob, or further back, Edna and Carol. Then there was the Long Island Express, or the Great New England Hurricane of 1938. The archival photo above shows flooding in Massachusetts; Maine was spared the worst of that storm, which remains a benchmark for the region.

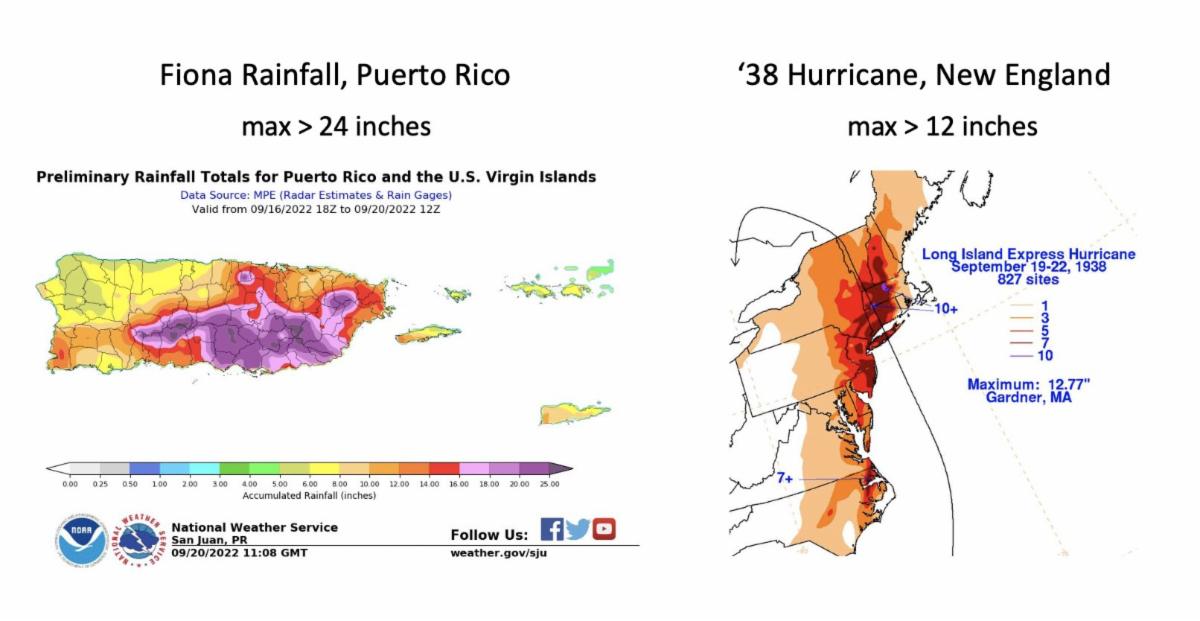

This is why I was struck by a Tweet I saw after Fiona hit Puerto Rico. Climate scientist Mathew Barlow of the University of Massachusetts-Lowell posted this comparison of rainfall during Fiona and the 1938 storm:

Twice as much rain fell on Puerto Rico during Fiona as New England saw in the worst of its worst-ever hurricane. It’s almost unimaginable.

“I had a couple of things in mind when making the comparison,” Barlow told me in a message Thursday. “1. People in the Northeast don’t always have a good sense of how much rain we can get from a tropical system. They’re not that common but set many of our records. 2. It’s kind of hard for us in the Northeast to also wrap our heads around just how much more rain those systems create when they’re still in the tropics (twice as much!). And they’re much more frequent there.”

And yet, as he points out, extreme precipitation is already a hallmark of climate change’s impacts in both the tropics and, relatively, New England.

“Neither region is prepared for the rainfall events that have already occurred, let alone for the increasing totals we’re already seeing and will continue to see as long as we continue to burn fossil fuels,” Barlow said.

Add that to Fiona’s potential to slam the Canadian Maritimes, he said, and this would be the point at which he’d try to offer his students some relief from climate dread with a cat meme.

It can all feel overwhelming, even just in local terms. Data analyzed by the nonprofit Climate Central shows that Maine’s rain events are getting more intense, more frequent and more costly, and the state Climate Council‘s reports show more frequent intense rains too, such as those storms in summer 2021 that washed out carriage roads in Acadia National Park. Parts of Maine are under flood advisories for heavy rain even as I write this.

The factors that determine the strength of the hurricanes (and nor’easters) we see are also changing. Waters in the Northeast and Gulf of Maine are warming and rising faster than most, adding fuel to storms that pass through. Barlow, on Twitter, pointed to research of his own from 2011 that showed hurricanes as a key factor overall in the rise of extreme precipitation in the Northeast.

It’s not the only climate impact we face. Short-term droughts appear to be on the rise at the same time as rain. Our summers are getting longer and hotter. Volatility and extremes are the new normal, here as everywhere — making a new benchmark hurricane for New England surely not a matter of if, but when.

But there is another reason I wanted to highlight that Fiona data this week. Sometimes, the climate story in a place like Maine is about what is not happening here. Fiona, just for this week’s example, will not bring Maine a fraction of the damage it’s done in Puerto Rico. Here, many of our climate impacts are a slower-moving disaster, less of an immediate existential threat. In fact, Maine could be a potential climate haven for folks migrating from places worse off (more on that in a future newsletter).

So as Puerto Rico struggles to recover from yet another catastrophic storm, I want to hold space for that, and for Maine’s role in a global climate system — for our contributions, say, from our disproportionate use of oil heating, to the emissions causing that system to heat up. It shouldn’t take a record-breaking hurricane here at home to convince Maine to do its part to help everyone else.

To read the full edition of this newsletter, see Climate Monitor: The past & future of New England hurricanes.

Annie Ropeik has been given the keys to the Climate Monitor newsletter while its regular author, the Monitor’s environmental reporter Kate Cough, is on leave until November. Reach Annie with story ideas at: aropeik@gmail.com.